100部最好的科幻电影之一

100部最好的科幻电影之二

100部最好的科幻电影之三

100部最好的科幻电影之四

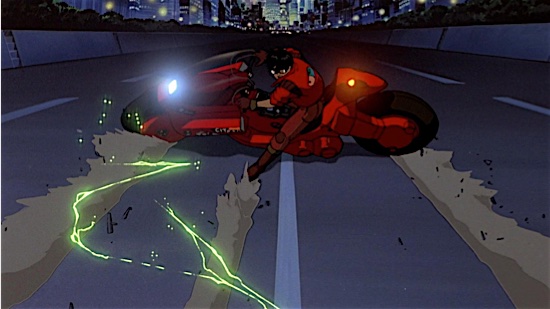

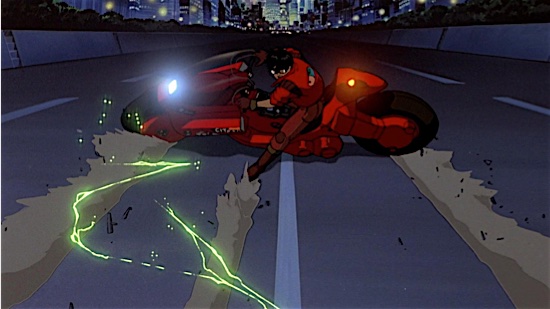

25.

Akira (1988)

Director:

Katsuhiro Otomo

The sum total of anime cinema from the early ’90s to present day is marked by the precedent of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira. Adapted from the early chapters of Otomo’s landmark manga series, Akira was the most expensive animated film of its time and a cinematic benchmark that sent shockwaves throughout the industry. Taking place 31 years after after World War III was sparked by a massive explosion that engulfed the city of Tokyo, Akira is set in the sprawling metropolis of Neo-Tokyo, built on the ruins of the former and teetering precariously on the cusp of social upheaval. The film follows the stories of Kaneda Shotaro and Tetsuo Shima, two members of a youth motorcycle gang whose lives are irrevocably changed one fateful night on the outskirts of the city. While clashing against a rival bike gang during a turf feud, Tetsuo crashes into a strange child and is promptly whisked away by a clandestine military outfit while Kaneda and his friends look on, helplessly. From then, Tetsuo begins to develop frightening new psychic abilities as Kaneda tries desperately to mount a rescue. Eventually the journeys of these two childhood friends will meet and clash in a spectacular series of showdowns encircling an ominous secret whose very origins rest at the dark heart of the city’s catastrophic past: a power known only as “Akira.”

Like Ghost in the Shell that followed it, Akira is considered a touchstone of the cyberpunk genre, though its inspirations run much deeper than paying homage to William Gibson’s Neuromancer or Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. Akira is a film whose origins and aesthetic are inextricably rooted in the history of post-war Japan, from the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and the “Anpo” student protests of that era to the country’s economic boom and the then-nascent counterculture of Bosozoku racing. Akira is a film of many messages, the least of which a coded anti-nuclear parable and a screed against wanton capitalism and the hubris of “progress.” But perhaps most poignantly, at its heart, it is the story of watching your best friend turn into a monster. Akira is almost single-handedly responsible for the early 1990s boom in anime in the West, its aesthetic vision rippling across every major art form, inspiring an entire generation of artists, filmmakers and even musicians in its wake. For these reasons and so many more, every anime fan must grapple at some point or another with Akira’s primacy as the most important anime film ever made. —Toussaint Egan

24.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

Director: Michel Gondry

In what might be Charlie Kaufman’s finest script, boy meets girl, unaware that they might be living out a doomed eternal recurrence. A brain-wipe firm allows its clients to erase choice people or events from their memory. Turns out, Joel (a repressed Jim Carrey) and Clementine (a vibrant Kate Winslet) have done this before. Technology is the Great Enabler and, perhaps, a secret destroyer—except that the science fiction aspect of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is just an auxiliary to the core relational dynami. Stripped of fantasy, the film’s theme is no Luddite cautionary tale but rather just a melancholy observation of human relationships. This is how it’s always been. We’re quite accomplished at failing each other…and ourselves.

There’s nothing so condemnatory as that statement in Eternal Sunshine, a film that watches and weeps at a whimsical circus breaking down. It immerses us in Joel’s mind, Gondry’s in-camera effects and nearly experimental editing taking us tumbling through the increasingly tragic process of removing Clementine. When I first saw this film in the theater in 2004, I swore I would never do the thing that Joel does to try to heal himself, but I’ve lived some life since then and now I’m not sure I can say the same. I’ve deleted phone numbers and pictures on Facebook, had about a month where I was vigilantly untagging myself; I’m sometimes scared to even look at my feed. It doesn’t matter what the social environment is, humans will use whatever’s available to mitigate pain, especially emotional pain. But sometimes we need the thing we want to be rid of; there’s no actualization without vulnerability, risk, and, inevitably, hurt. The final shot of Eternal Sunshine lingers in my memory, always on loop: Joel and Clementine, stumbling in play away from the camera, on a snowy beach in Montauk. It seems like an extrapolation of the final shot of The 400 Blows: “Stuck in stasis” has become “stuck in repeat.” And, yet, in that shot is acceptance, possibly even hope. There are no spotless minds, but perhaps some still can shine. —Chad Betz

23.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)

Director: Steven

Spielberg

Close Encounters was the personal project Spielberg wanted to pull off when he was able to establish himself as a Hollywood power player. The massive success of Jaws gave him the opportunity to realize his character-based, big budget, special-effects-driven science-fiction tale about humanity’s place in the galaxy, a rare optimistic and benign chronicle of first contact. The story of a father (Spielberg alter-ego Richard Dreyfuss) abandoning his family through obsession allowed Spielberg to deal with the inner demons related to his career, his own family and his upbringing by looking outward, boundlessly exploring the cosmos with outsized awe. —Oktay Ege Kozak

22.

Her (2013)

Director: Spike

Jonze

Spike Jonze’s colossal talent was far too great to remain trapped in MTV’s orbit; that became immediately clear when his breakout feature-length debut, Being John Malkovich, earned him an Oscar nod for Best Director. Following that minor postmodern masterpiece, he and screenwriter Charlie Kaufman continued their journey into solipsism with the hilariously unhinged Adaptation. As challenging, yet fun and accessible as Kaufman’s screenplays are, Jonze’s Her answers any lingering questions of whether those two movies’ (well-deserved) acclaim sprang solely from the power of Kaufman’s words. Retaining the sweetest bits of the empathetically quirky characters, psycho-sexuality and hard-wrung pathos of Malkovich, Her successfully realizes a tremendously difficult stunt in filmmaking: a beautifully mature, penetrating romance dressed in sci-fi clothes. Eye-popping sets and cinematography, as well as clever dialogue delivered by a subtly powerful Joaquin Phoenix, make Jonze’s latest feature one of the best films of 2013. It also serves as confirmation that—much like Her—the director is the complete package. —Scott Wold

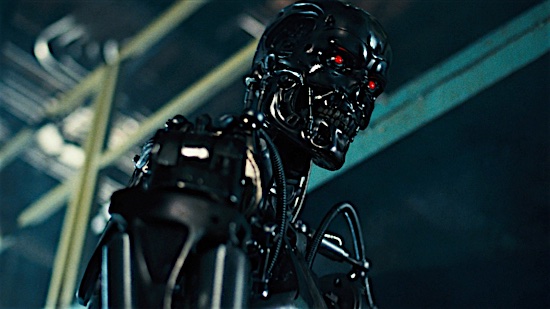

21.

The Terminator (1984)

Director:

James

Cameron

James Cameron’s first Terminator (and second feature) is less of a pure-popcorn action flick than its upscaled sequel, but that makes it all the more terrifying of a movie—dark, somber, replete with a silent villain who calmly plucks bits of his damaged face off to more precisely target its victims. The task in front of Kyle Reese (Michael Biehn) and Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) seems so insurmountable—even with a soldier from the future, going after the T-800 (Arnold Schwarzenegger, duh) with modern weapons is so ineffectual, it’s nearly comical. It’s as if Schwarzenegger is playing entropy itself—entropy seemingly a theme of The Terminator series, given the time-hopping do-overs, reboots and retreads since. You can destroy a terminator, but the future (apparently driven by box office receipts) refuses to be changed. —Jim Vorel

20.

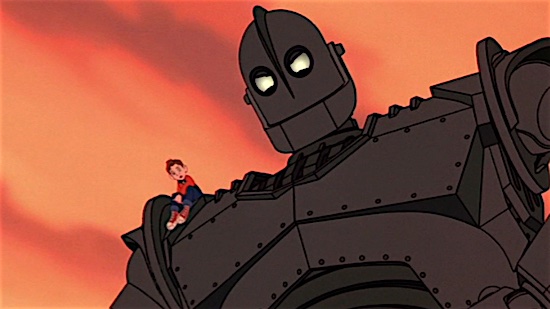

The Iron Giant (1999)

Director:

Brad Bird

Brad Bird’s feature debut championed traditional hand-drawn art at a time when computer animation was gaining in popularity, released by studio folk who didn’t realize just how special of a film they had on their hands, putting little to no marketing behind it. Luckily, The Iron Giant received its due recognition on home video. Set in the 1950s and drawing off of nuclear fears of the time—as well as Bird’s personal tragedy regarding gun violence—The Iron Giant incorporates the hallmark of the era’s science-fiction—a giant metal robot—into a touching coming-of-age story. Bird effortlessly moves between riotous comedy (such as young Hogarth’s efforts to hide his enormous new robot friend from his mother), high-spun action and poignant moments of fear and friendship. —Jeremy Mathews

19.

Jurassic Park (1993)

Director:

Steven

Spielberg

Jurassic Park , in 1993, was an achievement in major league filmmaking. Like Star Wars before it, it showcased a quantum leap in visual effects—both physical and CGI, in this case. Most important, however, were those CGI advancements. Jurassic Park, for better or worse, probably represents the first moment in our modern AAA Hollywood mythos in which an audience could look at CGI-driven creatures, nod their heads and simply accept them as part of the story. Married with one of the greatest pure adventure yarns in Spielberg’s celebrated canon, Jurassic Park was the spectacle we’ve come to expect of the traditional “blockbuster.” That loose term, since the days of Jaws, has always referred to a breed of films that are supposed to succeed by wowing us and making jaws drop. Jurassic Park did that in a way that infinitely raised expectations for every effects-driven money-maker—for everything—thereafter. —Jim Vorel

18.

Metropolis (1927)

Director:

Fritz Lang

Metropolis never slows as it delivers a constant stream of iconic images. Fritz Lang filled his parable with all the sci-fi/adventure tropes he could: the mad scientist, the robot, the rooftop chase, the catacombs and, as it turns out, a devious henchman. Metropolis, too, is a great reminder of just how difficult it is to judge an incomplete film. In fact, many silent films are missing material, even when it isn’t made clear in screenings or on home video. While Lang’s film has always been known for its spectacular special effects—it’s legally required that I use the phrase “visionary” while discussing it—not until a few years ago did modern audiences see a film anywhere close to the one that first premiered. It turned out that Metropolis’s best performance, Fritz Rasp as a ruthless spy for the corporate state, was part of that missing material, and it gives the film a greater sense of urgency, increasing the feeling of class-based antagonism. With that unknown excellence lurking in one of the most famous films of all time, it leaves us to wonder what else was lost in nitrate flames. —Jeremy Mathews

17.

Solyaris (1972)

Director:

Andrei Tarkovsky

In 2002, Steven Soderbergh adapted Stanislaw Lem’s classic science fiction novel into a perfectly fine and handsome movie. It’s the one time that the story of a Tarkovsky film has been duplicated, sharing source material, and it illustrates an important truth: Andrei Tarkovsky’s vision is singular, inimitable; it towers over all others. Where an accomplished director like Soderbergh made a serviceable sci-fi flick, Tarkovsky made visual poetry of the highest order.

Tarkovsky’s artistic instincts rarely failed him, and even though it was a big budget genre picture, Solyaris takes risks with the same confidence of expression and the same depth of resonance as any other Tarkovsky film. The science fiction concept of the titular planet-entity allows Tarkovsky a new angle at the same themes pondered in many of his works: the pivotal roles of history and memory in our present and future; the fraught responsibility of the individual in responding to the calls of the sublime; the struggle to know truth. Tarkovsky’s long-take, free-associative aesthetic was predicated on his philosophy of filmmaking as “sculpting in time,” and in Solyaris there is a fascinating confluence between the way time and perception is manipulated by Tarkovsky, and the way those things are manipulated by Solyaris itself. Solyaris gives back the protagonist, astronaut psychologist Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis), his dead wife Hari (Natalya Bondarchuk), for what purpose is unclear. But Tarkovsky’s films work in a similar fashion; difficult to say exactly why they do what they do, yet they pull at the deepest roots of our selves. They elicit emotional, meditative realities unlike any other. Like Kelvin’s resurrected Hari, the stimuli are simulacrums, symbols mined from a collective dream, but this does not diminish the worth of experiencing them. Sometimes they lead you to a place like Solyaris leads Kelvin: an island of lost memory—or perhaps of an impossible future, awash in the waters of some Spirit. That makes the unreal real; that gives the dream life. —Chad Betz

16.

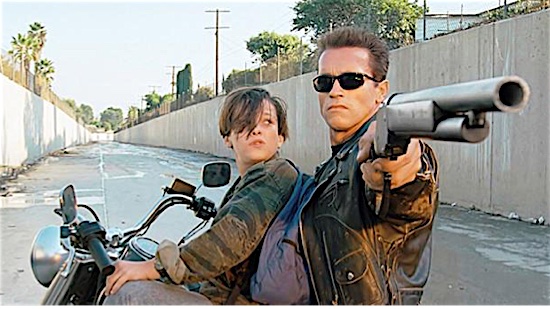

Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991)

Director:

James

Cameron

That rare sequel that trumps its predecessor, James Cameron and co-writer William Wisher Jr. crafted a near-perfect action-movie script that flipped the original on its head and let Ahnold be a good guy. But it’s Linda Hamilton’s transformation from damsel-in-distress to bad-ass hero that makes the film so notable. Why should the guys get all the good action scenes? —Josh Jackson

15.

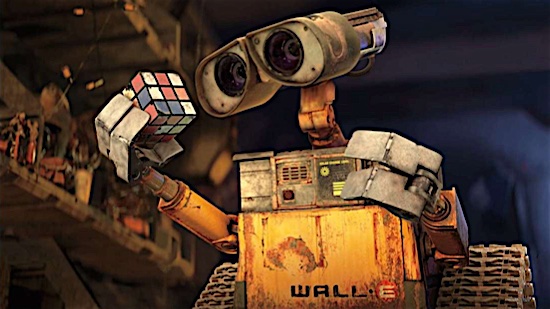

WALL-E (2008)

Director: Andrew

Stanton

Opening with 45 sublime minutes of almost no dialogue, WALL-E was a significant gamble for Pixar, whose remarkable string of successes to that point fell within a pretty narrow range. WALL-E rests firmly in the realm of children’s fantasy, but writer-director Andrew Stanton shooed the celebrity voices away from the center of the film and was clearly reaching toward something new. In a post-post-apocalyptic world where humans have gone into space and left behind an army of machines to clean up the place, 700 years have passed without much progress, and even the machines have fallen into ruin, except for one, a dilapidated ottoman-sized trash compactor named WALL-E who’s still honoring his directive and pining for a lost world. When WALL-E meets a gleaming white probe named Eve, their tentative relationship, like the rest of the film, evolves with few words. Even as the setting shifts to the ship containing the aforementioned humans and the rhythm shifts to action sequences with hazy goals, he film’s promise reduced to a well-executed but ordinary need for adrenaline, WALL-E is a noble experiment, lingering in the mind long after movies like Cars have faded. —Robert Davis

14.

Back to the Future (1985), Back to the

Future, Part II (1989) and Back to the Future,

Part III (1990)

Director: Robert Zemeckis

The three-part epic journey of Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox) and his legitimately insane mentor Doc Brown (Christopher Lloyd) not only provides the crucible through which practically every comedy-adventure made since must pass, it proves that even one insignificant kid’s actions make a universe of difference. There is little to add to a popular discussion of these films besides pointing out their diminishing returns with each successive entry, but that hardly takes away from the brilliance of Zemeckis’s storytelling. No plot point is wasted, no shot infused with anything less than humor and emotional breadth—if this sounds a bit schmaltzy, or a bit overboard with praise, then stop to consider how cherished these films are in the course of American cinema. As they mess with history, so too do they make history, and from that standpoint, it’s hard to imagine anyone feeling the need to go back to make this trilogy any better. —Michael Burgin

13.

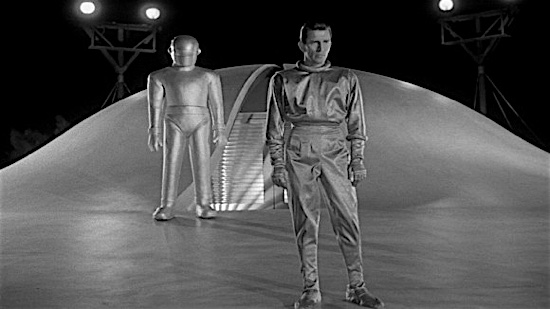

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951)

Director: Robert Wise

Robert Wise directed musicals (The Sound of Music), horror movies (The Haunting) and biopics (Somebody Up There Likes Me). But his finest film might have been The Day the Earth Stood Still, his 1951 pacifist parable (based on the Harry Bates short story “Farewell to the Master”) about the arrival of a UFO in Washington, D.C. This is no ordinary alien-invasion movie, though: The human-looking extra-terrestrial who emerges, named Klaatu (Michael Rennie), brings a message of warning that he wants to deliver to all the planet’s leaders. Instead, the military tries to imprison Klaatu, who escapes and goes undercover, befriending an unwitting mother (Patricia Neal) and her impressionable son (Billy Gray). If all you know of The Day the Earth Stood Still is “Klaatu barada nikto,” you’ll be amazed what a thoughtful, funny, smart movie this is: Wise produced one of Hollywood’s warmest sci-fi classics. And it’s approximately 1,000 times better than the 2008 Keanu Reeves remake. —Tim Grierson

12.

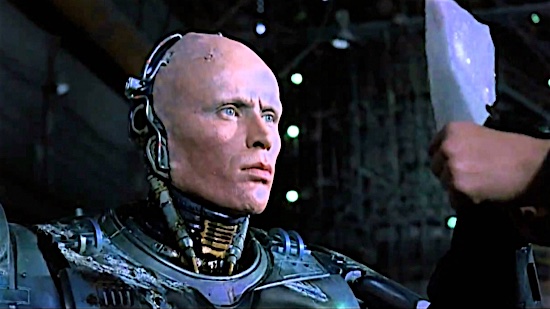

Robocop (1987)

Director: Paul

Verhoeven

Throughout the late-1970s and indulgent ’80s, “industry” went pejorative and Corporate America bleached white all but the most functional of blue collars. Broadly speaking, of course: Manufacturing was booming, but the homegrown “Big Three” automobile companies in Detroit—facing astronomical gas prices via the growth of OPEC, as well as increasing foreign competition and the decentralization of their labor force—resorted to drastic cost-cutting measures, investing in automation (which of course put thousands of people out of work, closing a number of plants) and moving facilities to “low-wage” countries (further decimating all hope for a secure assembly line job in the area). The impact of such a massive tectonic shift in the very foundation of the auto industry pushed aftershocks felt, of course, throughout the Rust Belt and the Midwest—but for Detroit, whose essence seemed composed almost wholly of exhaust fumes, the change left the city in an ever-present state of decay. And so, though it was filmed in Pittsburgh and around Texas, Detroit is the only logical city for a Robocop to inhabit.

A practically peerless, putrid, brash concoction of social consciousness, ultra-violence and existential curiosity, Paul Verhoeven’s first Hollywood feature made its tenor clear: A new industrial revolution must take place not within the ranks of the unions or inside board rooms, but within the self. By 1987, much of the city was already in complete disarray, the closing of Michigan Central Station—and the admission that Detroit was no longer a vital hub of commerce—barely a year away, but its role as poster child for the Downfall of Western Civilization had yet to gain any real traction. Verhoeven screamed this notion alive. He made Detroit’s decay tactile, visceral and immeasurably loud, limning it in ideas about the limits of human identity and the hilarity of consumer culture. As Verhoeven passed a Christ-like cyborg—a true melding of man and savior—through the crumbling post-apocalyptic fringes of a part of the world that once held so much prosperity and hope, he wasn’t pointing to the hellscape of future Detroit as the battlefield over which the working class will fight against the greedy 1%, but instead to the robot cop, to Murphy (Peter Weller), as the battlefield unto himself. How can any of us save a place like Detroit? In Robocop, it’s a deeply personal matter. —Dom Sinacola

11.

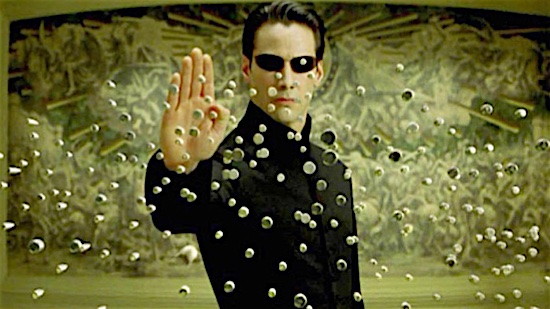

The Matrix (1999)

Directors:

The Wachowskis

There is little to add about what’s been already codified about the film that made cyberpunk not stupid—and therefore is the best cyberpunk movie of all time, amidst its many accomplishments—or that made Keanu Reeves a respectable figure of American kung fu, or that finally made martial arts films a seriously hot commodity outside of Asia. The Matrix is—next to the Wu-Tang Clan—what proved to a new generation that martial arts films were worth their scrutiny, and in that reputation is bred college classes, heroes’ journeys and impossible expectations for special effects. Even today we still have this film to thank for so much of what we love about modern kinetic cinema, about how malleable genius science fiction can be, about just how deeply our connection to mythmaking—to the religiosity of civilization’s symbols—can reach. This is our red pill; everything else is an illusion of greatness and everything else is an allusion to what the Wachowskis accomplished, including the two sequels—bloated and beautiful and unlike anything anyone could have expected from the relatively self-contained original—which in turn earned the distinction of setting the course for every multi-part franchise (i.e., Lord of the Rings and the MCU) to come —Dom Sinacola

10.

La Jetée (1962)

Director:

Chris Marker

At only 28 minutes, La Jetée is somewhere between a film and art piece. Its concept—black and white photos pieced together while an omniscient narrator explains what’s happening—quickly announces its symbolic purpose: a man (Davos Hanich), whose story we’re told as plainly as possible we are now a part of, can travel relatively painlessly through time because of a few stark images he’s carried with him since childhood. World War III has decimated Paris, reducing most citizens to desperate “guinea pig” status, used by Scientists to concoct time travel experiments “to call past and future to the rescue of the present.” Most of the helpless jerks launched through time end up going mad, unable to mentally “hold” themselves to a time their minds aren’t conditioned to endure. But the aforementioned man is stronger than them: He is “glued to an image of his past.” So how better can a filmmaker believably reproduce memory than obsess over the stillness of it? Rarely do we fixate on a whole detailed sequence, instead dwelling on one detail, one image branded into our brain tissue. The man’s is that of a pier (“la jetée”), someone dying in epic silhouette and a woman’s face. It’s that image that allows him to travel (without machine) through time, to visit our “present” in order to prevent his “future.” Like in Twelve Monkeys, Terry Gilliam’s upsetting re-imagining of Marker’s film, redirecting fate is easier said than done. As the man confronts his destiny, no other film since La Jetée has made the concept of time travel so personal, and the concept of time so sad. —Dom Sinacola

9.

Alien (1979)

Director:

Ridley Scott

Conduits, canals and cloaca—Ridley Scott’s ode to claustrophobia leaves little room to breathe, cramming its blue collar archetypes through spaces much too small to sustain any sort of sanity, and much too unforgiving to survive. That Alien can also make Space—capital “S”—in its vastness feel as suffocating as a coffin is a testament to Scott’s control as a director (arguably absent from much of his work to follow, including his insistence on ballooning the mythos of this first near-perfect film), as well as to the purity of both horror and sci-fi as cinematic genres. Alien, after all, is tension as narrative, violation as a matter of fact, using technology and imagination as powerful vessels for both. When the crew of the mining spaceship Nostromo is prematurely awakened from cryogenic sleep to attend to a distress call from a seemingly lifeless planetoid, there is no doubt the small cadre of working class grunts and their posh Science Officer Ash (Ian Holm) will discover nothing but mounting, otherworldly doom. Things obviously, iconically, go wrong from there, and as the crew understands both what they’ve brought onto their ship and what their fellow crew members are made of—in one case, literally—a hero emerges from the catastrophe: Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver), the Platonic ideal of the Final Girl who must battle a viscous, phallic grotesque (care of the master of the phallically grotesque, H.R. Giger) and a fellow crew member who’s basically a walking ziploc bag for an upsetting amount of seminal fluid. As Ripley crawls through the ship’s steel organs, between dreams—the film begins with the crew wakening, and ends with a return to sleep—Alien evolves into a psychosexual nightmare, an indictment of the inherently masculine act of colonization and a symbolic treatise on the trauma of assault. In space, no one can hear you scream—because no one’s really listening. —Dom Sinacola

8. Brazil

Taking place in a dystopic future a little goofier than the classic Orwellian version (though no less sinister), the world of Terry Gilliam’s 1985 film is the lovechild that results when bureaucratic nightmare meets escapist fantasy. The result is lyrical and beautiful, as well as horrific and haunting. Though decades of ill-fated and tumultuous productions lay ahead for the Monty Python alum, Brazil remains one of the purest and most palatable expressions of Gilliam’s unique vision. —Michael Burgin

7.

Under the Skin (2014)

Director:

Jonathan Glazer

It’s a rare feat for a film to successfully convey the voice of the Other. Especially when that voice is an Other to everyone else here on Earth. Loosely based on Michel Faber’s book of the same name, director Jonathan Glazer’s take on Under the Skin finds greater fascination with translating an otherworldly perspective than with the novel’s rather transparent “meat is murder” didactic. It not only makes for a more interesting story, it takes the form of an experience that reminds one of why the medium of film is so special. Taking place in present-day Scotland, both in and outside Glasgow, Under the Skin follows the alien-hijacked visage of a woman (Scarlett Johansson) as she stalks and separates men from the herd, luring them back to her lair to meet an oily doom. That’s merely the premise, though: Glazer’s film slowly emerges as a deeply curious meditation on what it means to be human. It might be a bit hyperbolic to consider it an apt companion piece to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, but it surely touches upon a similar investigative theme, only in reverse. And, wow, like Kubrick’s touchstone, Glazer’s movie, too, is a visual knockout, thanks to the stunning mixture of stillness and claustrophobic disorientation captured by cinematographer Daniel Landin. And as primal and affecting as the film’s imagery is, its score and sound design is more than a fitting match. Of course, any film whose story relies on a single actor—regardless of any other of its competencies—can still stumble and not recover if that actor’s performance falls flat. But Scarlett Johansson again proves she’s not merely another pretty face, even if that pretty face is an awfully useful tool in portraying a lethal seductress. Along her character’s journey from dispassionate serial killer to vulnerable human sympathizer, Johansson hits her marks with chilly precision. The casting of Johansson, too, proves additionally inspired; just as with David Bowie’s Thomas Newton in The Man Who Fell to Earth, the very nature of their iconic presence further distances the notion of mere actors-cum-aliens—they’re already elevated above the clouds in their stratospheric fame. —Scott Wold

6.

Stalker (1979)

Director: Andrei

Tarkovsky

“Once, the future was only a continuation of the present. All its changes loomed somewhere beyond the horizon. But now the future’s a part of the present.” So says the Writer (Anatoli Solonitsyn) in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, somewhere deep in the Zone, contemplating the deeper trenches of his subconscious, of his fears and life and whatever “filth” exists within him. “Are they prepared for this?” he asks. In Tarkovsky’s last Soviet film, the director seems to be admitting that what he’s feared most has come to pass.

What that means is of course nebulous for a viewer not steeped in the director’s life or in the history of the country that was both home and hostile to him and his work throughout most of his life. Based very loosely on Roadside Picnic, a novel by brothers Boris and Arkady Strugatsky (who also wrote the screenplay), Stalker imagines a dystopic future not far from our present—or Tarkovsky’s present, before the fall of the Berlin Wall or the devastation of Chernobyl—in which some sort of otherworldly force has deposited a place humans have called “the Zone” onto Earth. There, the laws of Nature don’t apply, time and space thwarted by the hidden desires and wills of all those who enter it.

Of course, the government has set up cordons around the Zone, and entry is strictly prohibited. Guides/liaisons called “stalkers” head illegal expeditions into the Zone, taking clients (often intellectual elites who can afford the trip) into the heart of the restricted, alien area—in search of, as we learn as the film slowly moves on, the so-called “Room,” where a person’s deepest desires become reality. One such Stalker (Aleksandr Kaidanovsky) is hired by the aforementioned Writer and a physicist (or something) known only as the Professor (Nikolai Grinko) to lead them into the Zone, spurred by vague ideas of what they’ll find when they reach the Room. The audience is as much in the dark, and through Tarkovsky’s (near-intolerably) patient shots, the three men come to discover, as do those watching their journey, what has really brought them to such an awful extreme as hiring a spiritual criminal to guide them into the almost certain doom of whatever the Zone has waiting for them.

And yet, no context properly prepares a viewer for the harrowing, hypnotic experience of watching Stalker. Between the sepia wasteland outside the Zone (so detailed in its grime and suspended misery you may need to take a shower afterwards) and the oversaturated greens and blues of the wreckage inside, Tarkovsky moves almost imperceptibly, taking the rhythms of industry and the empty lulls of post-industrial life to the point of making the barely mystical overwhelmingly manifest. Throughout that push and pull, there is the mounting sense of escape—of Tarkovsky escaping the Soviet Union and its restrictions on his films, maybe—as equally as there is the sense that escape should never be attempted. Some freedom, some knowledge, the director seems to say, isn’t meant for us. —Dom Sinacola

5.

Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (1977)

Director: George

Lucas

Before Star Wars, science fiction inhabited a vastly different cinematic landscape. Outside of a few films like John Carpenter’s Darkstar, these imagined realities tended to be pristine, shiny and generally fantastical. The Star Wars universe, on the other hand, dropped audiences into an already ongoing story, in a setting that felt incredibly thought out, organic and lived-in. Things get dirty. The Millennium Falcon is full of dents and dings, as worn as a real-world vehicle would be. It’s may be strange to use the word “realistic,” to describe the visual side of George Lucas’s space opera, but the setting for Star Wars simply felt more authentic than those that came before, and this is an often overlooked element of what made it a cultural phenomenon—along with, of course, its groundbreaking FX work. The people who really had their work cut out for them were filmmakers who wanted to do sci-fi in a post-Star Wars world. The bar of expectations had been raised to exponential heights. —Jim Vorel

4.

Aliens (1986)

Director:

James

Cameron

James Cameron colonizes ideas: Every beautiful, breathtaking spectacle he assembles works as a pointillist representation of the genres he inhabits—sci-fi, horror, adventure, thriller—its many wonderful pieces and details of worldbuilding swarming, combining to grow exponentially, to inevitably overshadow the lack at its heart, the doubt that maybe all of this great movie-making is hiding a dearth of substance at the core of the stories Cameron tells. An early example of this pilgrim’s privilege is Cameron’s sequel to Ridley Scott’s roughly-feminist horror masterpiece, in which Cameron mostly jettisons Scott’s figurative (and uncomfortably intimate) interrogation of masculine violence to transmute that urge into the bureaucracy and corporatism which only served as a shadow of authoritarianism—and therefore a spectre of the male imperative—in the first film. Cameron blows out Scott’s world, but also neuters it, never quite connecting the lines from the aggression of the Weyland-Yutani Corporation to the maleness of the military industrial complex, but never condoning that maleness, or that complex, either. Ripley’s (Sigourney Weaver) story about what happened on the Nostromo in the first film is doubted because she’s a woman, sure, but mostly because the story spells disaster for the corporation’s nefarious plans. Private Vasquez’s (Jennette Goldstein) place in the Colonial Marine unit sent to LV-426 to investigate the wiping out of a human colony is taunted, but never outright doubted, her strength compared to her peers pretty obvious from the start. Instead, in transforming Ripley into a full-on action hero/mother figure—whose final boss battle involves protecting her ersatz daughter from the horror of another mother figure—Cameron isn’t messing with themes of violation or the role of women in an economic hierarchy, he’s placing women by default at the forefront of mankind’s future war either for or against the ineffable forces of capitalism. It’s magnificent blockbuster filmmaking, and one of the first films to redefine what a franchise can be within the confines of a new director’s voice and vision, but below all of the wonderful genre-based imagination and splendor, Cameron doesn’t have much of anything to say. Still, it’s an awesome film despite itself, a tense action bonanza, and a pretty good reminder all these years and proposed Avatar sequels later that Cameron’s clearly decided on which side of the war he’s fighting. —Dom Sinacola

3.

Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back

(1980)

Director: Irvin Kershner

The Empire Strikes Back is Exhibit A in the category of sequels that surpass the original, taking the wondrous world we were granted in A New Hope and deepening, expanding its purview in every direction. It gives flesh to the idea of the “Rebel Alliance,” showing us how this ragtag band of freedom fighters operates while slowly winning the ideological battle and drawing more support to their cause. Every character undergoes positive growth: Leia (Carrie Fisher) moves from “princess” figurehead to military commander and tireless organizer of a resistance; Han (Harrison Ford) has become a leader of men, completing the transition he began when returning to help destroy the Death Star in A New Hope; and Luke (Mark Hamill) finally starts down the path to becoming a Jedi in earnest. His Dagobah scenes with Yoda are heavy with omens and portent; never in the series do the arcane mysteries of the Force feel as compelling as they do while Luke levitates rocks and digests philosophy. The mysticism and wonder of Star Wars are at their zenith in Empire.

Elsewhere, the series’ space-piloting scenes have their most goosebump-raising moment when the Falcon dodges asteroids and T.I.E. Fighters. The petty squabbles of the Imperial Navy and its never-ending parade of dead officers give us a glimpse into the structure of the enemy. A colorful array of bounty hunters is assembled. A classic romance blossoms. All builds to what is perhaps the biggest “oh my god!” reveal in cinema history, completely redefining the audience’s perception of all the events that led up to it. It’s hard to imagine that Empire will ever be toppled as the greatest Star Wars film of all time, but if it somehow is, that will indeed be a momentous disturbance in the Force. —Jim Vorel

2.

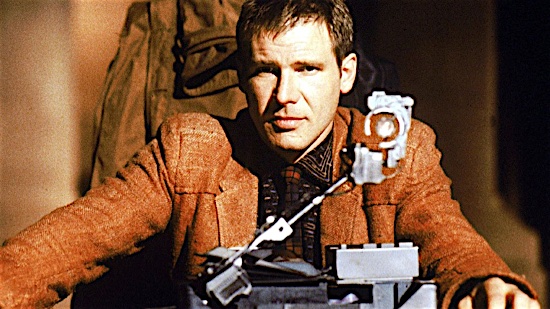

Blade Runner (1982)

Director:

Ridley Scott

Just as The Road Warrior set the look and tone for countless post-apocalyptic cinema-scapes to follow, so too did the world of Ridley Scott’s dingy, wet and overcrowded Blade Runner set the standard for the depiction of pre-apocalyptic dystopias. But he also had Harrison Ford, Sean Young, Rutger Hauer and a cast of actors who all bring this Philip K. Dick-inspired tale of a replicant-retiring policeman to gritty, believable life. Beneath the film’s impressive set design and inspired performances lies a compelling meditation on the lurking loneliness of the human (and, perhaps, inhuman) condition that continues to resonate (and trigger new creations, like Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049) to this day. —Michael Burgin

1.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Director:

Stanley

Kubrick

Fifty years ago, Stanley Kubrick told the story of everything—of life, of the universe, of pain and loss and the way reality and time changes as we, these insignificant voyagers, sail through it all, attempting to change it all, unsure if we’ve changed anything. Written by Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke (whose novel, conceived alongside the screenplay, saw release not long after the film’s premiere), 2001: A Space Odyssey begins with the origins of the human race and ends with the dawn of whatever comes after us—spinning above our planet, god-like, a seemingly all-knowing, hopefully benevolent fifth-dimensional space fetus—spanning countless light years and millennia between. And yet, despite its ambitious leaps and barely comprehensible scope, every lofty symbolic gesture Kubrick matches with a moment of intimate humanity: the sadness of a mighty intellect’s death; the shock of cold-blooded murder; the minutiae and boredom of keeping our bodies functioning on a daily basis; the struggle and awe of encountering something we can’t explain; the unspoken need to survive, never questioned because it will never be answered. So much more than a speculative document about the human race colonizing the Solar System, 2001 asks why we do what we do—why, against so many oppositional forces, seen and otherwise, do we push outward, past the fringes of all that we know, all that we ever need to know? Amidst long shots of bodies sifting through space, of vessels and cosmonauts floating silently through the unknown, Kubrick finds grace—aided, of course, by an epic classical soundtrack we today can’t extricate from Kubrick’s indelible images—and in grace he finds purpose: If we can transcend our terrestrial roots with curiosity and fearlessness, then we should. That the end of Kubrick’s odyssey returns us to the beginning only reaffirms that purpose: We are, and have always been, the navigators of our destiny. —Dom Sinacola