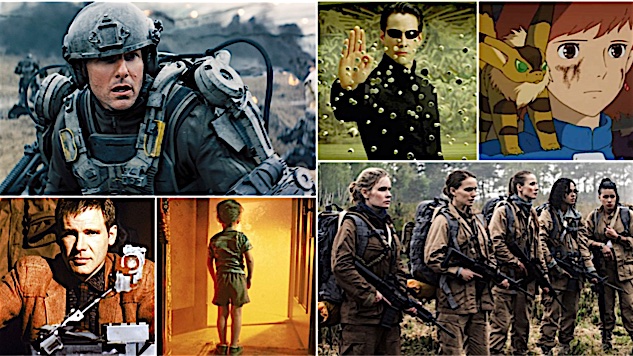

100部最好的科幻电影之一

100部最好的科幻电影之二

100部最好的科幻电影之三

100部最好的科幻电影之四

Much like its close genre cousin (nephew/niece?) the superhero film, the potential of cinematic science fiction exploded in the latter part of the 20th century thanks to technological advances that transformed special effects. Unlike superhero films, which were so stunted for so long that almost every new one makes it onto our updated 100 Best Superhero Films of All Time list, science fiction proved fertile ground for filmmakers before the likes of Industrial Light & Magic supercharged a director’s ability to exceed our imagination. Thus, this list, while filled with films from the ’80s onward, has its fair share of older films. Before we dive into it, though, let’s discuss a few things this list will not have (or at least, not have many of).

Superhero films are for the most part absent. Though so many superhero stories involve the stuff of science fiction—aliens, high-tech and strange worlds—there are plenty of great sci-fi movies to include on this list without bumping 20 of them off for DC and the MCU. (We’ve made an exception for one entry because the space opera underpinnings were too strong to ignore.) We’ve also left off, for the most part, the traditional giant monster/kaiju movie for the same reason. If you want a nice roundup of Godzilla’s greatest hits, check out our own Jim Vorel’s ranking of Godzilla’s cinematic oeuvre. (For the real kaiju rank-o-phile, Jim has also taken the measure of every Godzilla monster.) Finally, joining superheroes and kaiju on the sidelines, are the post-apocalyptic (and a few mid-apocalyptic) films. Though, again, there are a few exceptions, for the most part you will not find Mad Max here, or Eli, or even that guy who is Legend. (I see you frowning—“But will there be dystopias,” you ask? Hell yeah, we got dystopias.)

As you’ll see below, that leaves plenty of great films. As we go about our lives with appliances more powerful than the super computers of a few decades ago, take a few hours here and there to check out some of these you haven’t seen and to revisit some you have. Chuckle at those futuristic visions that now seem all too quaint, marvel at those that still blow your mind, and perhaps squirm uncomfortably as you watch those that strike a bit too close to home.

Here are the 100 best science-fiction movies of all time:

100.

A Trip to the Moon (1902)

Director:

George Méliès

While A Trip to the Moon only lasts 15 minutes, it still feels epic (plus, that runtime wasn’t considered so short in 1902). In turn, this light, colorful (make sure you watch the hand-painted, restored version) collage of whimsy follows a premise that would go on to serve sci-fi adventure films for more than a century: People embark on a journey and crazy shit goes down. With its long, stagy takes and flat compositions, the primitive nature of the film is apparent, but Méliès makes up for it with charm. Modern viewers instinctively know how to spot basic camera trickery, especially when perspective and scale aren’t quite right. Méliès, however, understood his limitations, embraced the artifice and, with that moon face taking a rocket to the eye, created something iconic. —Jeremy Mathews

99.

Alphaville (1965)

Director:

Jean-Luc Godard

Science-fiction isn’t particularly suited to Godard’s gaze—so erratic and tongue-in-cheek, so uninterested in the exigencies and peculiarities of world-building is the legendary French director—but there is also no better visionary to attack the mind-fuck that is this weirdo Lemmy Caution adventure. Alphaville is as much an experimental noir as it is speculative fiction, steeped in the tropes of the former while blissfully tinkering with the world of the latter, never quite justifying the hybridizing of both but never quite caring, either. As such, the pulpy story of a secret agent (Eddie Constantine) who’s sent into the “galaxy” of Alphaville to assassinate, amongst a few, the creator of the artificial intelligence (Alpha 60) which runs all facets of Alphavillian society by pretty much outlawing all emotion—meanwhile falling in love with the daughter of the inventor (Godard muse Anna Karina)—is as goofy as it is compelling, fully committed to the confusing premise and aware, as most Godard films are, of the leaps required of the audience to follow the meandering plot. Saturated with anachronism and stylized to the point of parody, Alphaville isn’t interested in immersing a viewer in a not-so-distant dystopian future as it is in laying bare science fiction as a genre which demands we dramatically re-conceptualize everything about the genre we take for granted: language, humanity and a future we’ll at least kind of understand. —Dom Sinacola

98.

Barbarella (1968)

Director:

Roger Vadim

Barbarella was a unique film when it was released in 1968, and it remains something very unusual as it celebrates its 50th anniversary: A blend of science fiction, fantasy and erotica that plays all three both campy and straight, depending on its mood. Appropriately, then, Jane Fonda’s Barbarella is a young space vixen trained in the “art of love,” but she’s also something of an ingénue without any experience in the real world. The film’s sets, costumes and production design rightfully earned attention upon its initial release, being fabulously lush and colorful, making for gothic but lascivious grandeur in space, and featuring Space Mutiny’s John Philip Law to boot. If Barbarella initially sold itself upon a vaguely defined promise of titillation, those artistic flourishes ended up proving more influential for the next generation of ’70s science fiction. Barbarella will likely never gain the respect it’s owed, but one could point to plenty of B-movies of its day to testify to the lasting impact it had on exploitation film and the tawdrier corners of sci-fi. —Jim Vorel

97.

Sleeper (1973)

Director:

Woody Allen

Sleeper’s sci-fi slapstick is Woody Allen comedy at the peak of the legendary filmmaker’s powers. Miles Monroe (Allen), as a cryogenically unfrozen man out of time, is drafted into an underground resistance movement against a tyrannical, robot-enforced police state. (In today’s political climate, its prescience feels eerie, if obvious.) What follows is pinpoint physical comedy, hilariously Allen-esque one-liners and some side-splittingly funny sight gags (not to mention the incomparably talented Diane Keaton) pervading the future dystopian America of 2173. Thankfully, for Miles, the police state of the future is evidently more incompetent than him. Would that we were so lucky today. —Scott Wold

96.

Stargate (1994)

Director:

Roland Emmerich

A pre-disaster-porn Roland Emmerich directed this (intentionally?) campy, conspiracy-minded sci-fi yarn—a film probably better remembered via the television franchise it spawned—and it’s an odd duck for sure. James Spader plays an Egyptologist savant who cracks the code to open the titular gate, while Kurt Russell growls at space aliens in the guise of ancient Egyptian deities. That right: Suck it, Ancient Egyptian engineers! You weren’t so clever after all; alien slavers built the pyramids before humans revolted and sent them packing to another planet! The rest of the movie is as bonkers as its setup, while Spader, the woman gifted to him (problematic!) and Russell leap to incredulous assumptions trying to make their way back home. But first, won’t some white savior please free the space Egyptians?! —Scott Wold

95.

The Brother from Another Planet (1984)

Director: John Sayles

During the ’80s, John Sayles established himself as a smart indie writer/director with a knack for social commentary, but only one of his films embedded said commentary into a zany sci-fi plot. The result is the story of a mute alien who looks like a black man with weird feet, who crash-lands in Harlem and meets and observes the people of New York City. Joe Morton gives a stellar silent performance that, like the film itself, seamlessly moves from comic to empathetic. —Jeremy Mathews

94.

Outland (1981)

Director: Peter

Hyams

Two years after Alien, Peter Hyams blew up the blue-collar subtext of Ridley Scott’s grimy mining vessel politics to remake High Noon in space. In perhaps his noblest role, Sean Connery plays Federal Marshal William O’Niel, a rigorous do-gooder assigned to duty shepherding the motley crew of titanium ore miners inhabiting a station on the Jupiter moon of Io. Like any burgeoning colony on the borders of civilization, law and order automatically succumbs to whatever criminal hierarchy supplies the vices required to prevent the workers from devolving into total madness—but nobody told O’Niel. Principled to a fault and still reeling from the sudden departure of his wife and son—fed up with one too many assignments to shitty outposts far away from an Earth their son has never seen—O’Niel decides to stand alone against the confederacy of capitalist evil saturating the already dysfunctional society slowly springing up on Io, led by by smarmy corporate boss Mark Sheppard (Peter Boyle). From there, Hyams stages a tense stand-off between O’Niel and the bureaucratic assassins sent to teach him what’s what (i.e., murder him) leading to a fatal game of cat and mouse in which O’Niel’s hopelessly outnumbered, though the cramped quarters and unforgiving void of space can be worked to his advantage. Rather than relegate the exploration of the cosmos to only the elite, Hyams (with directors like Scott and John Carpenter) serves as cinematic tributary for the proletariat, knowing that what awaits us off planet isn’t an escape from the institutionalized suffering of most of us on Earth, but a continuation of that human tragedy into a much more alien, unforgiving environment. The more it seems we’ll need to find a way to outlive this world—our world—the more we’ll have to come to terms with what we won’t be able to leave behind. —Dom Sinacola

93.

Moon (2009)

Director: Duncan

Jones

First-time director Duncan Jones is overt about his stylistic appropriations of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, right down to the sweeping orchestral music that frames the opening shots of the titular satellite and Earth. Yet, where Kubrick tapped into existential fears about human extinction and the future of civilization, Jones hypothesizes the logical conclusion of that dark vision: a world where the need for more energy has rendered humanity a manufactured cog of multinational corporations whose reach now extends beyond the boundaries of Earth. The film’s plot centers on Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell), the only human on a lunar mining facility that harvests Helium-3, a clean fuel that can meet a near-future Earth’s ballooning energy demands. Base computer system GERTY (Kevin Spacey) is his sole companion on Sam’s three-year caretaking mission, since a supposed satellite failure means he can only send and receive pre-recorded messages. When an accident nearly kills Sam, he’s saved by a clone of himself and begins to unravel the sinister nature of the base, and his existence. Moon cribs heavily from the retro-futuristic look of ‘60s and ‘70s sci-fi for its claustrophobic and sanitized depiction of the moon base, but this high-tech eye candy is only the backdrop to a larger morality tale about humanity’s ever-shrinking position within a technologically-saturated society. When the human experience can be synthesized (and thus made disposable), does such a thing as “humanity” even exist? There’s a host of challenging philosophical threads throughout—cloning, masculinity, energy, corporate power—but those individual issues complement rather than engulf the larger narrative. Moon is a superlative example of science fiction that hearkens to the genre’s roots: social commentary on the human condition, without the easy catharsis of overblown special effects and space opera. It’s the ultimate rarity in modern cinema: a mature, engaging and thoughtful sci-fi movie, and proof that there’s life yet left in the genre. —Michael Saba

92.

Galaxy Quest (1999)

Director:

Dean Parisot

Galaxy Quest is a film about equilibrium between love and parody; a movie made with less of the former and too much of the latter becomes a mean-spirited dunk on sci-fi fandom, and a movie made in the reverse becomes too much about fan service than honest-to-goodness storytelling. Dean Parisot, aided and abetted by writers David Howard and Robert Gordon, finds the perfect balance of both, and Galaxy Quest gets to be a straight-up sci-fi adventure flick that embraces its genre as enthusiastically as it pokes fun at its tropes. You don’t make that kind of affectionate self-satire without caring. It’s not like sci-fi fandom couldn’t stand a little dunking, after all, but only a real sci-fi fan knows where to draw the line.

So Parisot, Howard and Gordon must be real sci-fi fans. Much as Galaxy Quest picks away at the conventions of its category, and at the people who worship sci-fi with as much reverence as the average Baptist praises Jesus, it’s built on an abiding fondness for Star Trek: For phasers, for warp drives, for teleportation, for holograms, for alien races exotic and bizarre, for every other damn cliché in the sci-fi playbook that makes us groan but which we know we couldn’t quite live without. (What’s a good sci-fi movie without a brash, macho commander who makes questionable strategic calls that somehow work anyway?) This one’s for the sci-fi fans. And if you’re not a sci-fi fan, then it might be the movie to make you into one. —Andy Crump

91.

The Hidden (1987)

Director:

Jack Sholder

Though John Carpenter’s The Thing steeped the then-terrifyingly mysterious AIDS crisis in otherworldly horror five years before, The Hidden indulges in similar tropes and identical themes with blunter, no-less-pulpier mayhem. LA detective Thomas Beck (Michael Nouri) must reluctantly work with FBI Special Agent Gallagher (Kyle Maclachlan, pretty much playing a proto-Dale Cooper) to get to the bottom of a spate of violently incomprehensible murder sprees seducing otherwise normal, mild-mannered citizens—only to discover, when it’s much too late, that the culprit is an alien slug parasite passed orally from host to host, giving each unlucky husk superhuman vulnerability and a nihilistic mean streak. The sci-fi fare of the late ’80s too often succumbed to the cynicism of an overcommercialized zeitgeist, seeing in corporate America and the Reagan administration’s response to every social crisis the death knell of whatever good vibes speculative fiction once had to offer, but with The Hidden—violent and brutal in its own right—came, in the film’s final moments, a gesture of sacrifice and genuine compassion unusual for a genre flick of its ilk. Or, at least, that’s one way to interpret it. —Dom Sinacola

90.

Westworld (1973)

Director:

Michael Crichton

Long before there was Jurassic Park (or the increasingly frustrating Westworld HBO series, for that matter), Michael Crichton wrote (and directed) the story of another disastrous theme park: Delos, housing the sophisticated amusement android characters of Westworld, Medievalworld and Romanworld. After catastrophic malfunctions inevitably occur, a couple dudes enjoying Dude Time find themselves menaced for real, when the robotic “bad guy” Gunslinger’s safety measures disappear. And a decade before there was The Terminator, there was Yule Brenner’s implacable robot stalker, an unfeeling killing machine who happens to look exactly like Brenner’s heroic character from The Magnificent Seven. Don’t bother trying to melt his face, Peter (Richard Benjamin); there are plenty more where that came from. “Boy, have we got a vacation for you!” promises the ads for the park. They weren’t wrong. —Scott Wold

89.

Independence Day (1996)

Director:

Roland Emmerich

They pretty much don’t make action movies like Independence Day anymore, although if you ask someone who caught Independence Day: Resurgence, they’ll tell you that’s probably a good thing. Regardless, there’s a certain sheen to this particular brand of FX-driven pre-2000s disaster blockbuster, an earnestness of conviction in terms of clear-cut characters like Jeff Goldblum’s “David Levinson”—call it a willingness to believe that the audience will be 100 percent on board with a protagonist from the very beginning, rather than questioning his methods. As for the rest of the cast, we get a who’s who of ’90s delights, whether it’s an ascendant, wisecracking Will Smith—one year before Men in Black would cement him as leading man material—or Bill Pullman as the flyboy American president ready to deliver one of cinema’s greatest jingoistic addresses. Independence Day doesn’t shy away from its inspirations as pulp (it might as well be a remake of Earth vs. The Flying Saucers as far as the alien motivations are concerned) but it dresses up its Saturday morning cartoon plot with undeniably ambitious spectacle, even when viewed 20-plus years later. That exploding White House, not to mention the effortless camaraderie of Goldblum and Smith in all their scenes together, cement Independence Day among the most rewatchable sci-fi action films of the past two decades. —Jim Vorel

88.

Silent Running (1971)

Director:

Douglas Trumbull

A precursor to both Wall-E and Moon, Silent Running was the first feature directed by Douglas Trumbull, the special-effects wizard best known for his work on 2001: A Space Odyssey, Close Encounters of the Third Kind and The Tree of Life. Set on a spaceship hovering around Saturn, this meditative film concerns an interstellar greenhouse custodian named Freeman Lowell (Bruce Dern) who’s keeping watch over the last of Earth’s forests and wildlife. When Lowell is told to destroy his payload and return to Earth, he refuses, deciding instead to fake an accident and pilot his ship into the farthest reaches of space, where he and his living wards will be safe from human interference. Ecologically conscious, narratively simple, deeply affecting, Silent Running is one of those great lost gems of 1970s sci-fi. —Tim Grierson

87.

Strange Days (1995)

Director:

Kathryn

Bigelow

Before she reinvented herself as the director of award-winning docudramas, Kathryn Bigelow made her name directing crazy genre movies like Near Dark and Point Break. With all respect to Point Break, however, Strange Days remains Bigelow’s most compelling pre-War on Terror project. Written by Bigelow’s former husband James Cameron and Oscar-nominated screenwriter Jay Cocks, Strange Days is a pulpy, noir-influenced sci-fi pic in the vein of Blade Runner but with more high-octane action and a lot more nudity. Developed in the era of the videotaped Rodney King beatings and the L.A. riots, the film is set in a dystopian Los Angeles where people’s memories and experiences are recorded directly from their brains to sell on the black market. Anyone who has ever wanted to experience criminal activities or perverse sexual encounters can now do so without repercussions. The trouble begins when vice-detective-turned-black-marketer Lenny Nero (Ralph Fiennes) discovers a “snuff” disc depicting the brutal murder of an acquaintance. This disc leads him down a rabbit hole into the urban underground. At nearly two and a half hours, the film’s visual pyrotechnics and beautifully stylized performances provide more than enough ammunition to justify such excess. —Mark Rozeman

86.

Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016)

Director: Gareth Edwards

Gareth Edwards’ venture into a galaxy far, far away is the Star Wars film we never knew we needed. A triumphantly thrilling, serious-minded war movie, it’s incalculably stronger for the fact that it’s not the first chapter in a new franchise, but complete and self-contained (to the extent that any Star Wars film can be) in a way that no other Star Wars entry, other than A New Hope, is capable of achieving. It doesn’t “set the stage” for an inevitable next installment, and its characters are all the realer for the fact that they’re not perpetually sheathed in blasterproof Franchise Armor. I had no idea until I watched Rogue One how refreshing that concept would be.

Our protagonist is Jyn Erso (Felicity Jones), a plucky young woman whose brilliant scientist father (Mads Mikkelsen) has been controlled throughout her life by the Empire and coerced into designing superweapons of the moon-sized, planet-killing variety. Forced into adulthood on the fringes of the Rebel Alliance, she’s assembled a Jack Sparrow-esque rap sheet and, as the film begins, finds herself in Imperial prison on various petty charges. Sprung by the rebels (who all carry themselves like serious badasses, by the way), she’s sucked into a mission involving her father, the newly completed Death Star and a cast of resistance fighters and idealists all opposing the Empire in one way or another. It’s often been said that George Lucas’s original work mirrors the likes of Kurosawa and spaghetti westerns, and that’s never been more true than in Rogue One as it slowly assembles its team.

This is pretty far from the kid-friendly, fast-talking, joke-cracking bluster of John Boyega’s Finn in The Force Awakens, and any fears that Disney was trying to lighten the mood of the film by “inserting humor” via subsequent reshoots are positively unfounded. The droid character of K-2SO, voiced by Alan Tudyk, shoulders almost the entire load of comic relief, and although his funnier lines do occasionally seem out of place, they ultimately buoy the film with much-needed levity. Indeed, without those occasional chuckles, one might describe the film as positively dour—they’re well calculated to be just enough. What Rogue One is, most accurately, is what it was sold as all along: A legitimate war movie/commando story, albeit with some familial entanglements. —Jim Vorel

85.

Dark City (1998)

Director: Alex

Proyas

Alex Proyas’s magnum opus serves up a cerebral sci-fi extravaganza as filtered through the visual tropes of film noir and German Expressionism. A staggering achievement in imagination, Dark City, like clear predecessor Blade Runner, flopped at the box office only to be revived later as a beloved cult classic. The film casts Rufus Sewell as amnesiac John Murdoch who wakes up one night to discover that his city is (quite literally) under the manipulation of a band of mysteriously pale men in jet-black trench coats and fedoras. Along for the ride is Kiefer Sutherland as a crazed scientist and Jennifer Connelly as the femme fatale, our hero’s estranged wife.

One might also draw a straight line between this and The Matrix, released a year later. The similarities between the two films’ visual styles and themes of slavery, techno-rebellion and free will are nigh-impossible to miss, and many visual essays have been written specifically to compare the two movies. John Murdoch’s arc is only slightly less portentous than that of the prophesied One (Keanu Reeves) in The Matrix—both are seemingly normal men scooped up and thrust into a web of slowly untangling secrets while discovering that they possess special powers that will eventually allow them to defeat the puppetmasters who created their reality. The two films were even largely filmed at the same studio—Fox Studios Australia—and possess a similar green-tinged patina of unreality. Ultimately, Dark City is a bit more philosophically aloof than the popcorn-munching, easier to grasp Matrix, which is probably the reason the latter eventually became a cultural touchstone. But Dark City deserves to be seen, both on its own merits and as an exercise to see which of its sights may have lodged in the mind of the Wachowskis, waiting to be reborn in the next year’s blockbuster. —Mark Rozeman and Jim Vorel

84. A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

A.I. may be Spielberg’s misunderstood masterpiece, evidenced by the many critics who’ve pointed out its supposed flaws only to come around to a new understanding of its greatness—chief among them Roger Ebert, who eventually included it as one of his Great Movies ten years after giving it a lukewarm first review. A.I. represents the perfect melding of Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick’s sensibilities—as Kubrick supposedly worked on the story with Spielberg, and Spielberg felt obliged to finish after Kubrick’s death—which allows the film to keep each of their worst instincts in check. It’s not as cold or distant as Kubrick’s films tend to be, but not as maudlin and manipulative as Spielberg’s films can become—and before the ending is brought out as proof of Spielberg’s failure, it should be noted that the film’s dark coda was actually Kubrick’s idea, adamant that the ending not be meddled with moreso than any other scene. A closer inspection of the film’s themes reveal a much bleaker conclusion—and, no, those aren’t “aliens.” —Oktay Ege Kozak

83.

Guardians of the Galaxy (2014)

Director:

James Gunn

Director (and co-writer) James Gunn has taken the somewhat obscure team (to non-comic-book fans, at least) and kept the source material’s tone, attitude and bombastic settings intact. As the self-named Star-Lord, Peter Quill (Chris Pratt) presents viewers with a pretty irresistible amalgam of Han Solo, Mal Reynolds and Captain Kirk. (Pratt owns this role.) The scene-stealing duo of Rocket (voiced by Bradley Cooper) and Groot (voiced by Vin Diesel) also provides the latest reminder of how convincing mo-cap-aided CGI has become. (Within moments after being introduced to them, I was yearning for a Rocket and Groot buddy picture.) Frankly, it’s hard to compete with Quill, Rocket and Groot, but Drax (Dave Bautista) and Gamora (Zoe Saldana) don’t need to shine as brightly—unlike The Avengers, one doesn’t get the sense each team member’s time center stage is being meticulously measured. (One other important thing to note about Groot—he is Groot.) Marvel’s rambunctious entry into the space-opera genre—and the cornerstone of its “Cosmic Marvel” roster of characters and storylines—so perfectly embodies what the preceding months of hype and hope foretold that even its weak points feel almost like unavoidable imperfections—broken eggs for a pretty satisfying omelet. —Michael Burgin

82.

Inception (2010)

Director:

Christopher

Nolan

In the history of cinema, there is no twist more groan-inducing than the “it was all a dream” trope (notable exceptions like The Wizard of Oz aside). With Inception, director Christopher Nolan crafts a bracing and high-octane piece of sci-fi drama wherein that conceit isn’t just a plot device, but the totality of the story. The measured and ever-steady pace and precision with which the plot and visuals unfold, and Nolan mainstay wally Pfister’s gorgeous, globe-spanning on-location cinematography, implies a near-obsessive attention to detail. The film winds up and plays out like a clockwork beast, each additional bit of minutia coalescing to form a towering whole. Nolan’s filmmaking and Inception’s dream-delving work toward the same end: to offer us a simulation that toys with our notions of reality. As that, and as a piece of summer popcorn-flick fare, Inception succeeds quite admirably, leaving behind imagery and memories that tug and twist our perceptions—daring us to ask whether we’ve wrapped our heads around it, or we’re only half-remembering a waking dream.

Director Andrei Tarkovsky wrote a book about his philosophy towards filmmaking, calling it Sculpting in Time; Nolan, on the other hand, doesn’t sculpt, he deconstructs. He uses filmmaking to tear time apart so he can put it back together as he wills. A spiritual person, Tarkovsky’s films were an expression of poetic transcendence. For Nolan, a rationalist, he wants to cheat time, cheat death. His films often avoid dealing with death head-on, though they certainly depict it. What Nolan is able to convey in a more potent fashion is the weight of time and how ephemeral and weak our grasp on existence. Time is constantly running out in Nolan’s films; a ticking clock is a recurring motif for him, one that long-time collaborator Hans Zimmer aurally literalized in the scores for Interstellar and Dunkirk. Nolan revolts against temporal reality, and film is his weapon, his tool, the paradox stairs or mirror-upon-mirror of Inception. He devises and engineers filmic structures that emphasize time’s crunch while also providing a means of escape. In Inception different layers exist within the dream world, and the deeper one goes into the subconscious the more stretched out one’s mental experience of time. If one could just go deep enough, they could live a virtual eternity in their mind’s own bottomless pit. “To sleep perchance to dream”: the closest Nolan has ever gotten to touching an afterlife. —Michael Saba and Chad Betz

81.

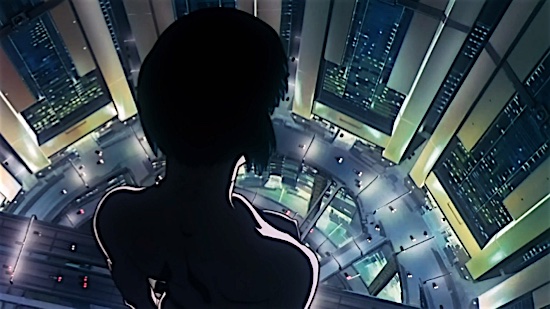

Ghost in the Shell (1995)

Director:

Mamoru Oshii

It’s difficult to overstate how enormous of an influence Ghost in the Shell exerts over not only the cultural and aesthetic evolution of Japanese animation, but over the shape of science-fiction cinema as a whole in the 21st century. When Ghost in the Shell first premiered in Japan, it was greeted as nothing short of a tour de force that would later go on to amass an immense cult following when it was released in the states. The film garnered the praise of directors such as James Cameron and the Wachowski siblings (whose late-century cyberpunk classic The Matrix is philosophically indebted to the trail blazed by Oshii’s precedent).

Adapted from Masamune Shirow’s original 1989 manga, the film is set in the mid-21st century, a world populated by cyborgs in artificial prosthetic bodies, in the fictional Japanese metropolis of Niihama. Ghost in the Shell follows the story of Major Motoko Kusanagi, the commander of a domestic special ops task-force known as Public Security Section 9, who begins to question the nature of her own humanity surrounded by a world of artificiality. When Motoko and her team are assigned to apprehend the mysterious Puppet Master, an elusive hacker thought to be one of the most dangerous criminals on the planet, they are set chasing after a series of crimes perpetrated by the Puppet Master’s unwitting pawns before the seemingly unrelated events coalesce into a pattern that circles back to one person: the Major herself.

Everything about Ghost in the Shell shouts polish and depth, from the ramshackle markets and claustrophobic corridors inspired by the likeness of Kowloon Walled City, to the sound design, evident from Kenji Kawai’s sorrowful score, to the sheer concussive punch of every bullet firing across the screen. Oshii took Shirow’s source material and arguably surpassed it, transforming an already heady science-fiction action drama into a proto-Kurzweil-ian fable about the dawn of machine intelligence. Ghost in the Shell is more than a cornerstone of cyberpunk fiction, it’s a story about what it means to craft one’s self in the digital age, a time where the concept of truth feels as mercurial as the net is vast and infinite. —Toussaint Egan

80.

District 9 (2012)

Director:

Neill

Blomkamp

Let’s begin with a number: 30 million. That’s how much money Neill Blomkamp spent to make District 9, a movie small in scale but great in ambition, look like it cost four times that amount. Years later, Blomkamp’s career hasn’t realized the full promise shown in District 9, but here, he looks like a guy knows what he’s doing all the same. A genre stew blended from varying measurements of Alien Nation, Watermelon Man, Independence Day, The Fly and RoboCop, District 9 treads familiar territory in an unfamiliar place, through an unfamiliar lens, splicing documentary-style filmmaking together with stomach-churning body horror and, by the end, high-end action spectacle.

Nine years ago, the end results of Blomkamp’s mad sci-fi cocktail felt revelatory. Today they feel disappointing, a remark on what he could have been and where his career might have taken him if he’d not lost himself in the morass of Elysium or turned off even his more devoted followers with Chappie. All the same, District 9 remains a major work for a first-timer, or even a third-timer, polished and yet scrappy at the same time; the film tells of an artist with something to say, and saying it with electric urgency. —Andy Crump

79.

Attack the Block (2011)

Director:

Joe Cornish

Written and directed by Joe Cornish, the sci-fi action comedy centers on a gang of teenage thugs—particularly their disgruntled leader, Moses, remarkably underplayed by a young John Boyega—and their housing project in South London. When the defiant juveniles take their crime to a new level and mug an innocent nurse (a delightful Jodie Whittaker), they immediately find themselves plagued by alien invaders. These hideous creatures, with their jet black fur and glowing blue fangs, want nothing more than to destroy the boys and their tower block.

In the spirit of Spielberg—even more so than J.J. Abrams’ Spielberg ode of the same year, Super 8—Cornish uses alien beings as the catalyst to bring supernatural redemption to a person and a community. He focuses specifically on London’s socioeconomic bottom half and the turmoil surrounding them, exposing the lies that society’s youth buy into that prolong cultural discontinuity. A comical scene, in which Moses tries to make sense of the aliens while giving excuses for his criminal behavior, highlights this cleverly—he doesn’t just blame the government for violence and drugs in his neighborhood, he blames the government for the whole alien invasion.

Cornish, however, doesn’t simply confront this hopeless attitude, he points toward hope—most vividly in the way Moses battles the aliens, his fight rapt with symbolic implications. Though he tries to escape the beasts through running and avoidance, he realizes he must inevitably face them, but not on his own. In Attack the Block, the alien invasion becomes one giant metaphor for the darkness that binds Moses, his friends and his block—a threat that can only be countered with the pivotal power of community. —Maryann Koopman Kelly

78.

Upstream Color (2012)

Director:

Shane Carruth

Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color builds a stunning mosaic of lives overwhelmed by decisions outside their control, of people who don’t understand the impulses that rule their every action. Told with stylistic bravado and minimal dialogue (none in the last 30 minutes), the film continually finds new ways to evoke unexpected feelings. The visuals—from stunning shots of underwater schist to microscopic photography—combine with extraordinary sound design and rhythmic cross-cutting to create a hypnotic portrait of the story’s intertwined narratives. The means to the interconnectivity is a small worm whose parasitic endeavors link lives together, but Carruth doesn’t bother with sci-fi exposition. The organism does what it does, and that’s all we need to know. This allows more time to explore the emotional impact the organism has on the characters. Ultimately, that’s where Upstream Color succeeds. An elaborate intellectual concept fuels the film, but a rich sense of humanity gives it power. —Jeremy Matthews

77.

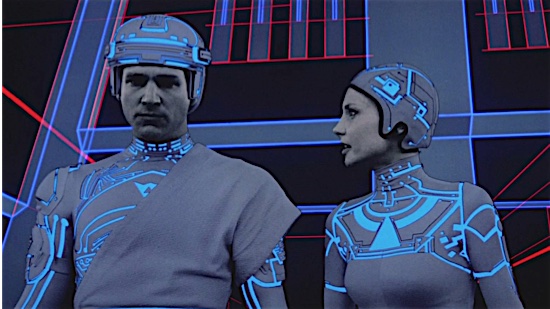

Tron (1982)

Director: Steven

Lisberger

In a movie in which computer programmers—so-called “users”—are revered as gods, no one really programs much of anything. It’s understandable: The early ’80s presented mind-boggling technology, once reserved for academics and elites, to the masses, and it all seemed like magic. Steven Lisberger’s Tron writes that awe into its code, building a world within a computer as a theocracy (populated by “programs” who carry out their existences serving a single function) ruled on religious oppression. The godhead is power-hungry AI MCP (Master Control Program) who, presaging James Cameron’s Terminator films, intends to surpass its human progenitors, the deified users, to take over the “real” world, making sinister moves like hacking into the Pentagon and the Kremlin and then being a cocky asshole about it. Suave engineer Flynn (Jeff Bridges) just wants credit for the video game he created, which turned ENCOM—the company he helped found as a forefather of the MCP—into an international juggernaut before his partner (David Warner) plagiarised him and kicked him from the top of the corporate ladder. Infiltrating the ENCOM building to try to dig up evidence of the betrayal, Flynn, just as annoying as the MCP, is digitalized, sucked into the company’s computer network via a laser (housed in “Laser Bay 1,” according to the buttons on the elevator), wherein, disguised as a program, he discovers just how fascist coding can get. And, like Neo in The Matrix, Flynn learns he can manipulate the fabric of this reality, taking up his new quasi-mystical role with relish, later going full be-robed Jedi bathed in beatific neon light for 2010’s Tron: Legacy. “All that is visible must grow beyond itself and extend into the realm of the invisible,” says Dumont (Barnard Hughes), an oracular figure and the closest the film gets to a digital priest. Tron, and so much of sci-fi, is a sign of just how spiritually charged that growth can be. —Dom Sinacola

76.

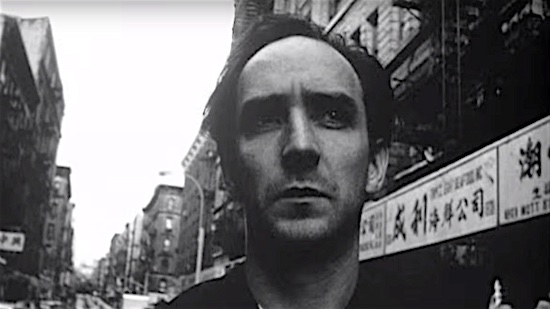

Pi (1998)

Director:

Darren

Aronofsky

Pi feels like an 85-minute migraine. That’s a good thing.

Darren Aronofsky, American master of the cinematic freakout, fittingly got his start with a film that brings us into the head of a man on the verge of a mental breakdown. For this guy, a math whiz named Max Cohen (Sean Gullette) who got his PhD at 20 and spends his days crunching numbers in a dingy New York apartment, the world is one big equation to be solved. Applying a mind quick enough to multiply 322 by 491 in a fraction of a second, Max intends on unlocking the patterns of the universe—the symmetries, recursions and ratios that will enable him to, among other things, predict the trajectory of the stock market, which he sees as an organism abiding by natural laws. For him, this quest is about pushing both technology and the human body further than they’ve ever gone before and so is, as is often the case with most sci-fi exploring the brink of understanding—of a new reality—hubristic in nature, though other parties intend to exploit his brain for different reasons. A posse of Wall Street big shots want to buy his stock market data to turn a profit, while a group of Hasidic Jews seek his help in deciphering the Torah, which they believe involves decoding the numerical basis of the Hebrew language. As outside interference and, above all, internal drive push Max to and beyond the brink of collapse, Pi seems on the verge of disintegrating with him, so closely does it hew to the man’s subjective experience.

To do this, the film shows us the things that a mentally-spent Max hallucinates: a singing subway passenger, a man with a bloodied hand and, most strikingly, a disembodied brain that literalizes the film’s own status as an externalization of its protagonist’s mind. These oneiric visions imbue the movie with a nightmarish aura evoking the surrealism of David Lynch. Appropriately, Pi’s most obvious Lynchian forebear is Eraserhead, given the Aronofsky film’s black-and-white aesthetic, otherworldly aura, slimy imagery, character of the alluring woman-next-door and grating soundtrack courtesy of Clint Mansell, whose hellish soundscape brilliantly evokes how tinnitus might sound if cranked to 11.

Three times throughout the film, Max recounts a childhood incident where his mom told him not to stare into the sun. He did anyway and impaired his vision as a result. The most obvious point of reference here is the myth of Icarus, the classic admonishment against unchecked ambition explicitly referenced elsewhere in the film, but also evoked is Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” which tells of an underground prisoner who, raised to believe that projected shadows on a wall were the original Things themselves, is freed from ignorance and allowed to step above ground into the light. In that story, the liberated man is blinded by sunlight after having spent his life in the dark, but with Max, what’s unclear is whether the sun is a transcendent truth or the fires of his own obsession obstruct the clarity that he’s been trying so hard to grasp. —Jonah Jeng