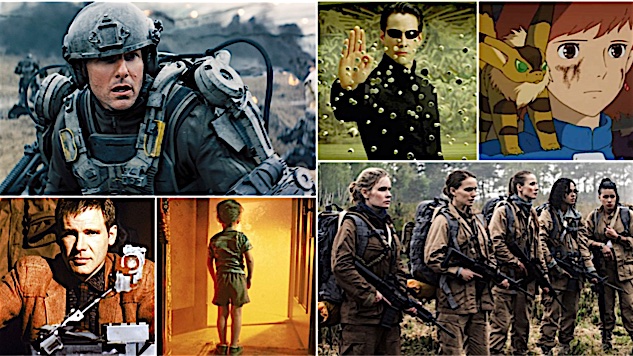

100部最好的科幻电影之一

100部最好的科幻电影之二

100部最好的科幻电影之三

100部最好的科幻电影之四

50.

World of Tomorrow and World of

Tomorrow – Episode Two: The Burden of Other People’s Thoughts

(2015; 2017)

Director: Don Hertzfeldt

In the first part, in 16 minutes, Don Hertzfeldt lays out humanity’s destiny: a vastly interconnected age of barely functional connections. In stick figures, impressionistic smatterings of vibrant color, geometric arrays, a snippet of a Strauss opera and the perspective of one little girl, Emily (Winona Mae), World of Tomorrow makes all science fiction to come before feel limited, not far-reaching enough—not enough. In 16 minutes. In any of the subjects that keep us up at night, that define us through our calamities—mental degradation, the loss of memory, nostalgia, cloning, AI, robotics, time travel, immortality, death, the incomparable loneliness of the universe—in Hertzfeldt’s deceptively simple animation, all is boiled down to an essence, a “yes” or “no” question: Why does simply being human push us farther and farther away from each other? Further and further away from ourselves? In the case of Future Emily falling in love with a mining robot, Hertzfeldt doesn’t want us to take it seriously so much as feel the pain, any pain, of Emily inevitably abandoning the robot to its long, blank eternity without her. In the case of hundreds of thousands of botched time travel missions killing time travelers by stranding them in an unknown time, or, worse, depositing them into the thinnest outer reaches of our atmosphere so their bodies fall back to earth, a beautiful nighttime show of falling stars, Hertzfeldt expects you to find this all pretty funny, because he knows you are using laughter to bury the urge to scream hopelessly into the indifferent void about just how meaningless your existence truly is. In 16 minutes: All of this—including a moment that will make your heart skip a beat because, in 15 minutes, you’ve become irrevocably attached to this little girl, Emily Prime, and you can’t bear the thought of leaving her, this little stick person cartoon, to face the universe alone.

Episode 2, a headier, longer (22 minutes) and altogether more ambitious continuation of the first film’s story of the endlessly replicating entity beginning with Emily Prime, revolves around a realization, uttered by Emily-6, a clone of the clone Emily Prime met in the first film: “If there is a soul, it is equal in all living things.” Emily-6 is more vessel, more of a vestigial being, than individual human, created as a backup for Emily’s memories, and so serving no functional purpose. She once again travels to the past to walk with Emily Prime, this time through Emily-6’s own psyche, hoping Emily Prime will be able to offer some context, some meaning, for everything she’s storing. At once, Hertzfeldt captures that disorienting distance between our memories and our sensation of inhabiting them, a distance that only grows wider and weirder with time, to the point that we may even doubt their veracity. And yet, these memories are the key to our immortality. Are our memories what make us human? What make our souls? Revisiting a moment in Emily’s life in which she kills a bug, realizing that bug is dead, no clones to replace it, just gone forever, Emily-6 grasps the futility of her own design. If there is a soul, she has one different from Emily Prime, different from the version of Emily upon which she’s based. The empathy of this moment, as is the case with so much of what Hertzfeldt’s accomplished in barely half an hour, is heart wrenching. —Dom Sinacola

49.

Paprika (2006)

Director:

Satoshi Kon

In a career of impeccable films, Paprika is arguably Kon’s greatest achievement. Adapted from the 1993 novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui (whose other notable novel, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, would form the basis of Mamoru Hosoda’s 2006 film of the same name), Kon could not have asked for source material that better suited his thematic idiosyncrasies as a director. Paprika follows the story of Atsuko Chiba, a psychiatrist working on revolutionary psychotherapy treatment involving the DC Mini, a device that allows the user to record and navigate one’s dreams in a shared simulation. By day Atsuko maintains an unremittingly cold exterior, but by night she moonlights as the film’s titular protagonist: a vivacious dream detective who consults clients on her own terms. When a pair of DC Minis are stolen and loosed upon the world, causing a stream of havoc which manifests the collective unconscious into the waking world, it’s up to Paprika and her colleagues to save the day. The summation of Kon’s decade-long career as a director, Paprika is a cinematic trompe l’oeil of psychedelic colors and exquisite animation. Kon’s transition cuts are memorable and mind bending, the allusions to his immense palate of cinematic influences are savvy, and his appeal to the multiplicity of the human experience as thoughtful and poignant as ever. Unfortunately, Paprika would turn out to be Kon’s last film, as he would later tragically pass away in 2010 from pancreatic cancer. One fact remains evident when looking back on the sum total of his life’s work: Satoshi Kon was, and remains, one of the greatest anime directors of his time. He will be sorely missed. —Toussaint Egan

48.

The Face of Another (1966)

Director:

Hiroshi Teshigahara

In some ways Hiroshi Teshigahara was a proto-Cronenberg, a sharp intellectual with a taste for pulp and the ability to dissect our affinities for the filth we drape around us. Body and psyche are always depicted in pulsing communion in Teshigahara’s films, and if Woman in the Dunes operated as a disarming vision of the sacrifice of transcendence to the hungers of human need (a thematic cousin to Cronenberg’s Shivers), then The Face of Another is about how the outer determines the inner—about our modularity, malleability and mundanity. It’s Teshigahara’s Dead Ringers.

And in Armageddon / Deep Impact mode, it came out the same year as the very similar Seconds. No bother, both movies rule: They are the Dead Ringers to each other, echoes of echoes about the echoes that make up our identity. Maybe that’s all identity ever was: a memory of a word that one’s body once spoke, that it still speaks, but maybe not always in the same voice, and maybe the word’s not what you once thought it was. In the beginning was the Word? “Yup,” says The Face of Another, barely stifling a scream.

Teshigahara’s rendering of Kobo Abe’s story strips a man of his face and gives him a new one. At some point we realize the man is gone, but also realize that we never knew him to begin with. In 2014’s Phoenix, Christian Petzold uses a similar premise to construct a melodrama. Nothing of that sort interests Teshigahara, however. At their harshest, his pictures are cold, still horrors; at their most tender, elegies for the existential. The Face of Another is both. —Chad Betz

47.

Annihilation (2018)

Director:

Alex Garland

Annihilation is a movie that’s impossible to shake. Like the characters who find themselves both exploring the world of the film and inexplicably trapped by it, you’ll find yourself questioning yourself throughout, wondering whether what you’re watching can possibly be real, whether maybe you’re going a little insane yourself. The film is a near-impossible bank shot by Ex Machina filmmaker Alex Garland, a would-be science fiction actioner that slowly reveals itself to be a mindfuck in just about every possible way, a film that wants you to invest in its universe yet never gives you any terra firma to orient yourself. This is a film that wants to make you feel as confused and terrified as the characters you’re watching. In this, it is unquestionably successful. This is a risky proposition for a director, particularly with a big studio movie with big stars like this one: This is a movie that becomes more confusing and disorienting as it goes along. Garland mesmerizes with his visuals, but he wants you to be off-balance, to experience this world the way Lena (Natalie Portman) and everyone else is experiencing it. Like the alien (I think?) of his movie, Garland is not a malevolent presence; he is simply an observer of this world, one who follows it to every possible permutation, logical or otherwise. It’s difficult to explain Annihilation, which is a large reason for its being. This is a film about loss, and regret, and the sensation that the world is constantly crumbling and rearranging all around you every possible second. The world of Annihilation looks familiar, but only at first. Reality is fluid, and ungraspable. It can feel a little like our current reality in that way. —Will Leitch

46.

Primer (2004)

Director: Shane

Carruth

Primer does not operate as most movies do, practically reverse-engineered to demand repeat viewings in order to, at the very least, figure out what is even going on. Shane Carruth—who wrote, directed, starred in, edited and scored the film on an impossible budget of $7,000—is, more than a decade after Primer premiered, still a rarity in the studio system, able to create groundbreaking films totally outside that system while trusting in the intelligence of his audience to trust that he’s got everything under control. The difficulty in untangling Primer’s labyrinthine time-travel plot falls in Carruth’s approach: Limited (or perhaps inspired) by a non-existent budget, Carruth shaved his story down to its basest elements, providing exposition in overheard conversations, offering practically nothing in the way of a narrative map to follow, vying instead to explore as mundanely as possible how two software engineers would wield the unthinkable power of time travel. While it may frustrate many uninterested in translating this kind of metaphysical visual language, Carruth’s film aims for more transcendent awards: Navigating Primer feels, we can only imagine, as Carruth’s characters would feel on the precipice of the completely unexplored unknown. That, for all its distancing tactics and opaque conundrums, Primer still operates on a deeply human level, is Carruth’s truest success. Upstream Color may be a sign that Carruth will only get better, but Primer is still a modern landmark of science fiction filmmaking: A story about the mysteries of reality revealed to the only most ordinary—living the most ordinary lives—among us. —Dom Sinacola

45.

Arrival (2016)

Director: Denis

Villeneuve

Your appreciation of Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival will hinge on how well you like being led astray. It’s both the full embodiment of Villeneuve’s approach to cinema and a marvelous, absorptive piece of science fiction, a two hour sleight-of-hand stunt that’s best experienced with as little foreknowledge of its plot as possible. Fundamentally, it’s about the day aliens make landfall on Earth, and all the days that come after—which, to sum up the collective human response in a word, are mayhem. You can engage with Arrival for its text, which is powerful, striking, emotive and, most of all, abidingly compassionate. You can also engage with it for its subtext, should you actually look for it. This is a robust but delicate work captured in stunning, calculated detail by cinematographer Bradford Young, and guided by Amy Adams’ stellar work as Louise Banks, a brilliant linguist commissioned by the U.S. Army to figure out how the hell to communicate with our alien visitors. Adams is a chameleonic actress of immense talent, and Arrival lets her wear each of her various camouflages over the course of its duration. She sweats, she cries, she bleeds, she struggles, and so much more that can’t be said here without giving away the film’s most awesome treasures. She also represents humankind with more dignity and grace than any other modern actor possibly could. If aliens do ever land on Earth, maybe we should just send her to greet them. —Andy Crump

44.

Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

Director:

Denis Villeneuve

The debate between what makes something “real” or not has become a staple of adult-minded sci-fi fare in the three-plus decades since Ridley Scott made one genre masterpiece after another dithering over the same debate, but the strength of Blade Runner 2049 is in how intimately Villeneuve (and writers Hampton Fancher and Michael Green) attempt to have us experience this world through the unreal eyes of a Replicant, K (Ryan Gosling). Ideally, we are forced to think about what “humanity” is when empathy—caring for these robots—is the natural result of the filmmakers’ storytelling.

Revisiting Blade Runner, one may realize that there isn’t much of a story there. The same could be said for Dick’s novel, as well as many of his novels: There is breathtaking world-building, impressive use of language and speculative ideas expanded and thought out to thoroughly conceived ends, but our characters are just people existing in this world, and Blade Runner is really just the story of a cop hunting down four dangerous criminals. 2049, despite its heavy themes and heavier exposition, is about a cop who must find a very special robot before the evil mega-corporation does. The brilliance of Blade Runner, and now its sequel, is that the majesty of the imaginations behind them—the sheer sci-fi magnanimity on display—is enough to bind us to these characters. To care about them.

Blade Runner 2049, then, is undoubtedly the most gorgeous thing to come out of a major studio in some time. Roger Deakins has inculcated Jordan Cronenweth’s lived-in sense of a future on the brink of obsolescence, leaning into the overpowering unease that permeates the monolithic Los Angeles Ridley Scott built. The scale of the film is only matched by the constant dread of obscurity—illumination shifts endlessly, dust and smog both magnifying and drowning the sense-shattering corporate edifices and hyper-stylized rooms in which humanity retreats from the moribund natural world they’ve created. There is a massive world, a solar system, orbiting this wretched city—so overblown that San Diego is now a literal giant dump for New L.A.’s garbage—but so much of it lies in shadow and opacity, forever out of reach. What Scott and Cronenweth accomplished with the original film, placing a potboiler within a magnificently conceived alternative reality, Villeneuve and Deakins have respected as they prod at its boundaries. There’s no other way to describe what they’ve done other than to offer faint praise: They get it. —Dom Sinacola

43.

Starship Troopers (1997)

Director:

Paul Verhoeven

Glistening agitprop after-school special and gross-ass bacchanalia, Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers delights in the ultraviolence it doles out in heavy spurts—but then chastises itself for having so much fun with something so wrong. Telling the story of a cadre of extremely attractive upper-middle-class white teens (played by shiny adults Casper Van Dien, Denise Richards, Nina Meyers, Jake Busey and Neil Patrick Harris) who get their cherries popped and then ground into hamburger inside the abattoir of interstellar war, Verhoeven cruises through the many tones of bellicose filmmaking: hawkish propaganda, gritty action setpieces and thrilling adventure sequences, all of it accompanied by plenty of gut-churning CGI, giant space bugs and human heads alike exploding without shame or recourse or respect for basic physics and human empathy. As much a bloodletting of Verhoeven’s childhood trauma, forged in the fascist mill of World War II Europe, as a critique of Hollywood’s cavalier attitude toward violence and uniformly heroic depictions of the military, the sci-fi spectacle can’t help but arrive at the same place no matter which angle one takes: geeked out on some hardcore cinematic mayhem. —Dom Sinacola

42.

Planet of the Apes (1968)

Director:

Franklin J. Schaffner

“What will he find out there, doctor?”

“His destiny”

That’s what the conservative ape scientist Dr. Zaius (Maurice Evans) tells compassionate ape “veterinarian” Dr. Zira (Kim Hunter) at the end of the original Planet of the Apes, as misanthropic astronaut George Taylor (Charlton Heston) sets out into the Forbidden Zone of this topsy-turvy planet—where intelligent, talking apes are the dominant species and humans are dumb beasts—in order to find out what really happened to his species. Unless you were living under a rock for the last 50 years, you know exactly what he will find.

But why does Zaius call this literally earth-shattering revelation Taylor’s destiny, and not his past, which is technically the case? The answer for that lies within Zaius’s role in the ape society. Unlike all other apes, Zaius knows the history of the painful and complex relationship between apes and humans. He knows how humans’ natural attraction to war, persecution, prejudice and cruelty sealed their eventual doom, and is (perhaps vainly) attempting to keep that “intellectual virus” from spreading to his beloved apes. He knows that once an intelligent human like Taylor has a chance to restart yet another attempt at civilization for his species, the same ugliness and destruction that comes with his inner nature will certainly plague his descendants. Therefore, he knows that Taylor will find both his past and his future on that beach.

Today, the Planet of the Apes franchise is still going strong. The timeless appeal of these films stems from the fact that they explore high-concept themes, like the inherent viciousness and frailty of human nature, with brutal clarity, told with a refreshing lack of condescension and philosophical hand-holding. By presenting a fable world where what we now consider to be animals are dominating humankind, they hold a mirror to our ugliness, arrogance and, just maybe, our chance for redemption.

Every installment and reiteration of the franchise contains a handful of characters who struggle to go against their basest urges and strive to bring compassion and peace to their kind. Yes, these films never forget to cultivate the value of hope for a peaceful world, but they’re never naïve enough to attempt to sell the audience on the idea that it’s an easy feat—as evidenced by the unfortunately yet appropriately bleak endings found in most of them.

The one that started it all is still the epitome of the Planet of the Apes experience. Co-written by Twilight Zone co-creator Rod Serling, the sci-fi fable structure of the novel’s adaptation fits Serling’s sensibilities so impeccably that the original Planet of the Apes might be the closest we’ll ever get to a single-story, feature-length Twilight Zone movie, creating a kind of balanced synergy between pure genre excitement and level-headed morality tale. —Oktay Ege Kozak

41.

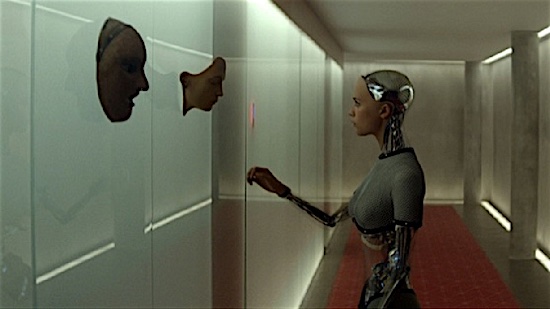

Ex Machina (2015)

Director:

Alex Garland

While popular science-fiction films have taught us that, no matter what we do, robots that become self-aware will eventually rise up and kill us, recent advances in artificial intelligence in the real world have confirmed something much seedier about the human imperative: If given the technology to design thinking, feeling robots, we will always try to have sex with them. Always. Alex Garland’s beautifully haunting film seems to want to bridge that gap. Taking cues from obvious predecessors like 2001: A Space Odyssey and AI—some will even compare it to Her—Ex Machina stands solidly on its own as a highly stylized and mesmerizing film, never overly dependent on CGI, and instead built upon the ample talents of a small cast.

The film’s title is a play on the phrase deus ex machina (“god from the machine”), which is a plot device wherein an unexpected event or character seemingly comes out of nowhere to solve a storytelling problem. Garland interprets the phrase literally: Here, that machine is a robot named Ava, played by Swedish actress Alicia Vikander, and that nowhere is where her creator, Nathan (Oscar Isaac), performs his research and experiments. Ava is a heavenly mechanical body of sinewy circuitry topped with a lovely face, reminiscent of a Chris Cunningham creation. Her creator is an alcoholic genius and head of a Google-like search engine called Bluebook which has made him impossibly rich. Enter Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), who is helicoptered in after winning a lottery at work for which the prize is a week at Nathan’s house. Nathan also intends to use Caleb to conduct something of a Turing test on steroids with Ava to determine if she can truly exhibit human behavior.

In fact, Ex Machina seems designed around the performances of its excellent mini-ensemble. Vikander especially finds the perfect balance between prosthetic personality and genuine empathy, enhanced by the film’s own teetering between some wonderfully titillating and creepy moments: Caleb watching Ava disrobe over a monitor, revealing her metal and circuitry; Nathan and his other sex-bot performing a jarringly synchronized disco dance; and Caleb losing his shit and questioning his own humanity with the help of a razor blade. It’s an awfully attractive film, too, appropriately seductive—no doubt designed to provoke conversations about the morality inherent in “creating” intelligence—as well as whether it’s cool to have sex with robots or not. —Jonah Flicker

40.

World on a Wire (1973)

Director:

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Those still banging the drum for The Matrix’s apparent “innovation” should reserve a four-hour slot for Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s ornate science-fiction drama World on a Wire, and discover that the idea of our world as a simulation (within a simulation, within a simulation …) had already been covered 26 years prior. Only recently revived as a “lost classic” of Fassbinder’s, it’s hard to imagine how forward-thinking World on a Wire must have appeared at the time, originally airing on German television in 1973. A technical director for a company that’s created a simulation of an entire world within its computers, Dr. Fred Stiller (Klaus Lowitch) investigates personally after his colleagues begin to disappear, and the people around him insist those now missing never actually existed at all. Framed beautifully among the mirrors and tacky futurist décor of early 1970s Germany, the film’s styled like the paranoid thrillers that were so popular at the time, only here the distrust grows epidemically—from initially incorporating Stiller’s associates, then the government, to eventually including Stiller’s fellow citizens and the very world he lives in. The fashion has aged; the ideas haven’t. —Brogan Morris

39.

Predator (1987)

Director: John

McTiernan

For all of the jokes and terrible impersonations made over the decades at the expense of Arnold Alois Schwarzenegger, during his peak throughout the ’80s, the actor possessed a certain joie de vivre unmatched by any action performer in Hollywood (with the possible exception of Bruce Willis). Schwarzenegger’s impish charm contrasts beautifully with his larger-than-life, muscle-bound physique, a dynamic he’s always happy to entertain. But Predator is one of the films of his heyday that dared to conjure a threat that even the specter of Schwarzenegger might not be able to conquer, a space-traveling alien trophy hunter who assembles a grisly collection of skulls and spinal columns throughout. It’s a basic premise that was utterly run into the ground by copycat B movies in the years to follow, but none of them come close to replicating the hyper-macho camaraderie that makes Predator an enduringly entertaining relic of its time. The sophomoric banter between the likes of Jesse Ventura, Carl Weathers and Shane Black is what sets the film apart, infusing it with a somehow endearing gentleman’s club mentality, fully aware of its inherent stupidity. We want to see this merry band of special forces operatives conquer the faceless chameleon set against them. There’s wry satire here about America’s attitude toward meddling in the affairs of less-developed nation states, but more than anything, Predator is simply one of the ’80s ’ best games of cat and mouse. —Jim Vorel

38.

Seconds (1966)

Director: John

Frankenheimer

Of all the films on this list, one of those with the world closest to ours can be found in John Frankenheimer’s Seconds. Setting the tale from coast to coast in prosperous ’60s America, Frankenheimer casts an eye through a thin veil of science fiction to what he sees as a failingly lonely way of life. Approached by a mysterious outfit known as “the Company,” middle-aged family man Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph) is given the opportunity to fake his death and start over as bohemian California-based painter Tony Wilson (Rock Hudson). Tapping away to the existential core, however, “Tony” only finds his new life as hollow as his old one, a construct populated by Company actors and other “reborns” who just want to sustain the illusion. James Wong Howe’s shadow-infused cinematography and Jerry Goldsmith’s anxious horror score apply the paranoid sheen to what is really a bleak examination of the contemporary domesticated worker—bleak because, minus the presence of the elusive, amoral Company, Seconds’ dystopian Earth is really our own. —Brogan Morris

37.

The Fifth Element (1997)

Director:

Luc

Besson

The Fifth Element is the ultimate display of what would happen if someone with the sci-fi enthusiasm of a teenage boy wrote a big-budget Hollywood script: Set in 23rd century New York City, taxi driver Korben Dallas (Bruce Willis) gets wrapped up in saving the world with his passenger Leeloo (Milla Jovovich), the fifth and final “element” that is needed to protect Earth. Along with The Chronicles of Riddick and the Star Wars films, Besson’s big dose of imagination is one of the purer cinematic representations of the space opera. Entertaining, thrilling and visually fantastical, The Fifth Element seemed to be the first sign of Besson coming into his overblown own. —Caitlin Colford

36.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978)

Director: Philip Kaufman

There’s no real need for the film’s credit-limned intro—a nature-documentary-like sequence in which the alien spores soon to take over all of Earth float through the cosmos and down to our stupid third berg from the Sun—because from the moment we meet health inspector Matthew Bennell (Donald Sutherland) and the colleague with whom he’s hopelessly smitten, Elizabeth Driscoll (Brooke Adams), the world through which they wander seems suspiciously off. Although Philip Kaufman’s remake of Don Siegel’s 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers begins as a romantic comedy of sorts, pinging dry-witted lines between flirty San Franciscan urbanites as Danny Zeitlin’s score strangely lilts louder and louder overhead, Kaufman laces each frame with malice. Oddly acting extras populate the backgrounds of tracking shots and garbage trucks filled with weird dust fluff (which we eventually learn spreads the spores) exist at the fringes of the screen. The audience, of course, puts the pieces together long before the characters do—characters who include Jeff Goldblum at his beanpole-iest and Leonard Nimoy at his least Spock-iest—but that’s the point: As our protagonists slowly discover that the world they know is no longer anything they understand, so does such simmering anxiety fill and then usurp the film. Kaufman piles on more and more revolting, unnerving imagery until he offers up a final shot so bleak that he might as well be punctuating his film, and his vision of modern life, with a final, inevitable plunge into the mouth of Hell. —Dom Sinacola

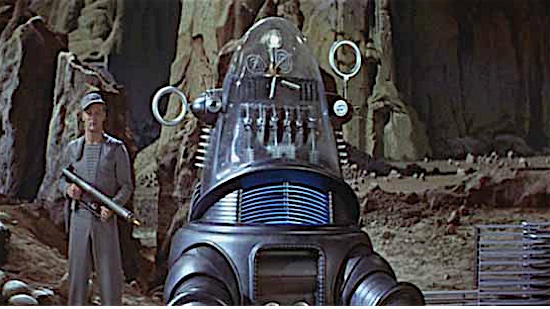

35. Forbidden Planet (1956)

Forbidden Planet is a rarity in a decade of low-budget B-movie sci-fi. Made by MGM Studios—and working as a narrative retread of Shakespeare’s The Tempest—this is high-quality, intelligent science fiction, featuring state-of-the-art special effects. A ship of American astronauts lands on an alien planet where the inhabitants are trying to safeguard the ruins of a previous civilization. Famous for its iconic “Robby the Robot”—more complex and intelligent than most of its automated screen predecessors—Forbidden Planet stands head and shoulders above most science fiction of the ’50s. —Andy Crump

34.

Total Recall (1990)

Director:

Paul Verhoeven

Very loosely based on the Philip K. Dick short story “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” (and aren’t all PKD adaptations “very loose”?), Total Recall functions as a construct for Paul Verhoeven to take a high-concept premise about memory implants and lost identity and motivational uncertainty and turn it into an Arnold Schwarzenegger schlock-fest. It should be bad, but it’s not; it should be, at best, cheesy fun—but it’s even more than that. Unlike many of it’s sci-fi action peers, Total Recall never runs out of steam or ideas; it starts with the memory implant stuff, but on the back end gives us a vividly imagined Mars society with an oppressed mutant population (which is, like, the best special make-up effects portfolio ever) and a secret alien reactor that’s a MacGuffin but also a deus ex machina. The plot’s a mess but so is Arnold. It all works.

Total Recall’s $60 million production budget was absolutely huge for its time, but unlike similar Hollywood ventures that put money towards glitz (like the 2012 remake, so slick it slips right out of one’s head), Verhoeven uses the loot to give us more dust, more grit, more decrepit sets, more twisted prosthetics and maximum Arnold. Verhoeven, in fact, uses Arnold as much as he uses anything else in the budget to tell this darkly exuberant story, from the contorted confusion of the set-up right on through to the eye-popping finale. It results in a sci-fi screed written in the form of a hundred Ahh-nuld faces, absurd and unforgettable. For as many times as Dick has been adapted, this is perhaps the one time the go-for-broke energy and imagination of his work has made it into the cinema (Blade Runner is something else entirely). Total Recall may have little in common with the actual content of the story it blows up, but it knows the vibe. And PKD vibes are the best kind. —Chad Betz

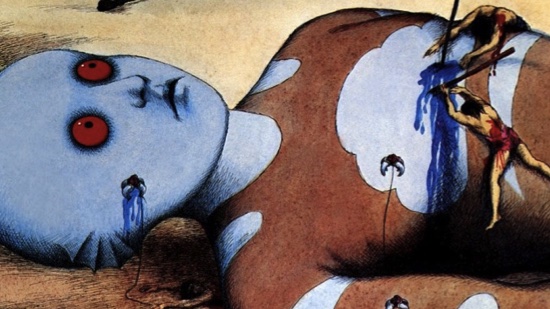

33.

Fantastic Planet (1973)

Director:

René Laloux

It doesn’t matter if you’re watching René Laloux’s excellent, eccentric Fantastic Planet for the first time or the fortieth, under the influence or stone sober: The film is such a one-of-a-kind oddity in cinema that each viewing feels like its own wholly unique experience. Put simply, there’s nothing quite like it. If you’ve yet to see this masterwork of 1970s psychedelia-meets-social-commentary, you’re missing out. If you have seen it, chances are you haven’t seen anything quite like it since, because there isn’t much in animated cinema to match it. The closest you’ll get is Terry Gilliam’s paper strip animation stylings in Monty Python’s Flying Circus, or maybe the still painting approach of Eiji Yamamoto’s Belladonna of Sadness. Neither of these equate with Fantastic Planet’s visual scheme, though, which just underscores its individuality. Where does a movie like Fantastic Planet come from? How does it even get made? Laloux has offered few answers over the years, though the documentary Laloux Sauvage holds some insight into how his mind works. Maybe the answers aren’t worth pursuing in the first place, and maybe the best way to understand Fantastic Planet is just to watch it, and then watch it again. —Andy Crump

32.

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Director:

Stanley

Kubrick

As with most (well, probably all) of Stanley Kubric’s book-to-screen adaptations, A Clockwork Orange remixes several aspects from Anthony Burgess’s novel, and probably for the better (at least Alex [a terrifyingly electric Malcolm McDowell] isn’t a pedophile in Kubrick’s film, for example). It’s still a relentlessly vicious satire portraying a society permissive of brutal youth culture, one where modern science and psychology are the best countermeasures in combating the Ultra Violence ™ that men like Alex and his fellow “droogs” commit. It’s painfully clear that when Alex is cast as a victim by the British Minister of the Interior (Anthony Sharp) that—spoiler alert!—evil wins. Christ, can any of us ever hear ”Singing in the Rain” the same again after this nightmare? —Scott Wold

31.

The Thing (1982)

Director:

John

Carpenter

No disrespect to the classic Christian Nyby/Howard Hawks version of The Thing from Another World from 1951, but John Carpenter’s 1982 reimagining of that story into The Thing is one of cinema’s greatest acts of modernization. In a manner that was mimicked six years later by Chuck Russel’s remake of The Blob, Carpenter took a thinly veiled Cold War allegory and cloaked it in his taut, atmospheric style, ratcheting up both suspense and the lurid payoff delivered by groundbreaking FX work, while expanding the mythology and capabilities of the titular monster. Every frame is a visual puzzle: Carpenter’s camera drifts over empty hallways, open door frames and cloaked figures in the arctic air. Who is The Thing, and more contentiously, when and how did they become The Thing? To this day, the theories spiral endlessly into dark corners of the internet, as Carpenter’s visual clues and Bill Lancaster’s script seem to provide the audience with most—but never quite all—of the information they need to be certain. Rob Bottin delivers what may be the literal zenith of practical effects in the history of horror cinema during The Thing’s several transformation scenes, and particularly in the mind-blowing sequence featuring the severed head of Norris (Charles Hallahan) sprouting legs to become a crab-like creature, which then attempts to scuttle away. The film is an artifact of big-budget ’80s horror purity: a thing of next-level special effects, mind-expanding mystery, masterful direction and the awesomeness that is Kurt Russell as the cherry on top. —Jim Vorel

30.

Je t’aime, je t’aime (1968)

Director:

Alain Resnais

Claude (Claude Rich) can’t successfully commit suicide, so instead he commits himself to the abyss of time. As in the case in Chris Marker’s La Jetée and, later, in Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (which Gondry admitted was inspired in part by Resnais’ film), the passage of time is experienced as the sum total of one’s memories—splayed like guesstimated data points across the illusory y-axis of our lives—and so beholden to the whims and tenuous subjectivity of our neuroses, our chemicals and, most of all, our nostalgia. Depressed and sunk into a kind of existential shock after the death of his wife, Claude submits to an extremely experimental time travel device concocted by a shadowy, private research cadre. Like Marker’s time machine, Resnais’ technology seems to take place mostly in the head of the protagonist, crafting his vessel more like a desert yurt ripe for a vision quest (replete with bean bag chair and administered “medicine,” presented as perhaps only semantically distinct from something like Ayahuasca) than a transportational pod—though Claude’s body does physically un-stick in time. Intended to only go back for minutes to experience small shards of space-time, Claude does not, as is usually the case, experience the sojourn the scientists meant him to, recycled and regurgitated through ever-random moments in his life which, taken together, flesh out the truth and tragedy behind the truth and tragedy Claude’s convinced himself is real. A master class in film editing, Je t’aime, je t’aime wallows in the impermanence of love, all the more painful, and all the more timely, for it. —Dom Sinacola

—Dom Sinacola

29. Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982)

Come for the “KhaaAAHHHHHN!” and stay for the surprisingly emotional treatise on aging without wisdom—as well as one hell of a potent, humbling gut punch of an ending. Anyone arguing for any other film in the Trek franchise will find themselves speaking into a black hole chewed in the matte canvas by exquisitely potent villain, played by Ricardo Montalban. That director/co-writer also Nicholas Meyer somehow coaxes a performance from William Shatner that’s only barely un-Kosher makes this movie a space opera with broad, lasting appeal. —Scott Wold

28.

They Live (1988)

Director:

John

Carpenter

Like most of John Carpenter’s movies, They Live can be read however one pleases—they are, after all, mostly about pleasing you. A sharp commentary on consumerism carved gleefully with a dull knife, or maybe something closer to a concerned embrace of the bourgeois joys inherent in dumb violence, or maybe just a weird-ass sci-fi action movie with a weird-ass leading man: They Live is, almost inherently, a joy to watch. It’s as if Carpenter’s tapped into some sort of primordially aligned pleasure axis along your spine, giving you the tingles as he balances insight and idiocy throughout his tale about a drifter (“Rowdy” Roddy Piper) who, with the help of magic sunglasses, discovers that the rich and powerful are just as grotesque as he’d always assumed. Every one of Carpenter’s odd plot choices click into place as if preordained, so that when Piper’s in a completely pointless, six-minute fight scene with Keith David, one can’t help but love that Carpenter’s in on the punchline with all of us, which just happens to be that there is no punchline. The fight scene exists for its own sake—as maybe much of They Live does. Carpenter’s a goddamn genius. —Dom Sinacola

27.

The Fly (1958; 1986)

Directors:

Kurt Neumann (1958) and David Cronenberg (1986)

Between The Blob, The Thing and The Fly, the ’80s were a magical decade for remaking already iconic ’50s horror/sci-fi movies. The original Kurt Neumann/Vincent Price version of The Fly is sometimes waved away as nothing more than a “camp classic,” but it’s a substantial film that is often more mystery than it is horror—a tightly focused narrative hinging around the question of why a woman has confessed to messily crushing her husband to death in a hydraulic press. Vincent Price is as entertaining as the fly-crossed scientist as you would no doubt expect him to be. The Cronenberg version, like the remake of The Blob, takes that basic premise and dresses it in both gallows humor and body horror, Jeff Goldblum’s researcher literally watching pieces of his body gelatinize and melt away in front of him. As “Brundle” he’s full of manic energy, ingenuity and eventually insectoid-enhanced physicality. Along with The Thing, the film is one of the last great hurrahs of the practical effects-driven horror era, featuring some of the more disgusting makeup and gore effects of all time. After seeing a man-sized Brundlefly vomiting acid, it’s difficult to ever look at a common housefly in the same way again. —Jim Vorel

26. E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

Steven Spielberg’s classic is many things: an ode to friendship that resonates with child and adult alike, one of the top-grossing films of all time, and the moment his career, on a scale of 1-10, reached 11. Though the Academy would not award Spielberg the Best Director trophy until there were more Nazis involved, E.T. remains perhaps the most deft expression of his directorial hand, interweaving all the usual “alien visitation” tropes with that most shared of human experiences—childhood—until the sci-fi of it all seems less important than the humanity portrayed. —Michael Burgin