100部最好的科幻电影之一

100部最好的科幻电影之二

100部最好的科幻电影之三

100部最好的科幻电影之四

75.

Looper (2012)

Director: Rian

Johnson

Joseph-Gordon Levitt channels his inner badass to act as the younger version of Bruce Willis, nailing (with the help of some CGI and prosthetics) Willis’s ubiquitous action presence. The best case made on film for “If time travel is outlawed, only outlaws will have time travel!”, writer/director Rian Johnson wisely treats the tech as a given, focusing instead on the dramatic scenarios humans’ use of it would create. The result is one of the more thrilling time-travel-infused flicks of the last few decades, and one obvious reason why Johnson was trusted with a Star Wars film not long afterward. —Christian Becker

74.

The Truman Show (1998)

Director:

Peter Weir

Peter Weir’s delightful, hilarious The Truman Show wouldn’t get made anymore. It’s a star-studded event film centered around a simple and dystopian premise: Jim Carrey’s eponymous character has unwittingly been raised from birth as a reality TV star and only now has begun to suspect that everybody in his life is a hired actor. Carrey’s clear-eyed acting is worlds away from the zany roles that catapulted him to fame a few short years prior, though, as was typically the case with Carrey roles in the ’90s, copious amounts of special effects work go toward creating a believable simulated reality for Carrey’s endearing everyman to be trapped within. The heartfelt monologues and devastating revelations as he fights to escape his gilded cage shine all the brighter for it. The fight to break away from control, from a sanitized and curated existence dictated by a literal white father figure in the sky, rings alarmingly two decades years later, when social media has made performative brand managers of us all. Truman is an unlikely and often hapless hero in his own story, but his eventual hijacking of his own narrative—and his final defiance of his literal and figurative creator figure—form one of the most heroic cinematic arcs of the last 20 years. —Kenneth Lowe

73.

The Chronicles of Riddick (2004)

Director:

David Twohy

Space Opera. So easy to dismiss, yet, as with many of the pulpy confections of the imagination, so hard to get just right. Fifth Element gets it right. Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets gets it wrong (though just wrong). David Twohy and Vin Diesel’s sequel to Pitch Black, however, is cooked to perfection, with noir-tinged dialogue and distress, existential threats both personal and planet-wide, and outlandish events and crazy characters presented with earnestness. The Chronicles of Riddick avoids exposition overload, though it manages to sneak in plenty of world-building, as our titular Furian kicks antagonist ass from one scene to the next. In some ways, the series as a whole can be compared to the Alien franchise—the first film horror, the second all action, the third, well, less exciting—but the second film of the series stands out as one of the purest, most enjoyable encapsulations of space opera outside the land of Lucas. —Michael Burgin

72.

Okja (2017)

Director: Bong

Joon-ho

Okja takes more creative risks in its first five minutes than most films take over their entire span, and it doesn’t let up from there. What appears to be a sticking point for some critics and audiences, particularly Western ones, is the seemingly erratic tone, from sentiment to suspense to giddy action to whimsy to horror to whatever it is Jake Gyllenhaal is doing. But this is part and parcel with what makes Bong Joon-ho movies, well, Bong Joon-ho movies: They’re nuanced and complex, but they aren’t exactly subtle or restrained. They are imaginative works that craft momentum through part-counterpart alternations, and Okja is perhaps the finest example yet of the wild pendulum swing of a Bong film’s rhythmic tonality.

Okja is, in other words, the culmination of Bong’s unique rhythms into something like a syncopated symphony. The film opens with Tilda Swinton’s corporate maven Lucy Mirando leering out an expository dump of public relations about her new genetically created super-pigs, which will revolutionize the food industry. We’re also introduced to Johnny Wilcox, played by Gyllenhaal as a bundle of wretched tics, like there’s a tightly-wound anime character just waiting to rid itself of its Gyllenhaal flesh, but in the meantime barely contained. Okja is the finest of the super-pigs, raised by a Korean farmer (Byun Hee-bong) and his granddaughter Mija (Ahn Seo-hyun), an orphan. Okja is Mija’s best friend, a crucial part of her family. Bong takes his sweet time with this idyllic life Mija and Okja share. The narrative slows down to observe what feels like a Miyazaki fantasy come to life. Mija whispers in Okja’s ear, and we’re left to wonder what she could possibly be saying. The grandfather has been lying to Mija, telling her he has saved money to buy Okja from the Mirando corporation. There is no buying this pig; it is to be a promotional star for the enterprise. When Johnny Wilcox comes to claim Okja (a sharp note of dissonance in the peaceful surroundings) the grandfather makes up an excuse for Mija to come with him to her parents’ grave. It is there he tells her the truth.

Mija’s quest to rescue Okja brings her in alliance with non-violent animal rights activists ALF, which ushers the film into a high-wire act of an adventure where Bong’s penchant for artful set-piece is pushed to new heights. The director works with an ace crew frontlined by one of our greatest living cinematographers, Darius Khondji, who composes every frame of Okja with vibrant virtuosity. The very action of the film becomes action that is concerned with its own ethics. As the caricatures of certain characters loom larger, and the scope of the film stretches more and more into the borderline surreal, one realizes that the Okja is a modern, moral fable. It’s not a film about veganism, but it is a film that asks how we can find integrity and, above all, how we can act humanely towards other creatures, humans included. The answers Okja reaches are simple and vital, and without really speaking them it helps you hear those answers for yourself because it has asked all the right questions, and it has asked them in a way that is intensely engaging. —Chad Betz

71.

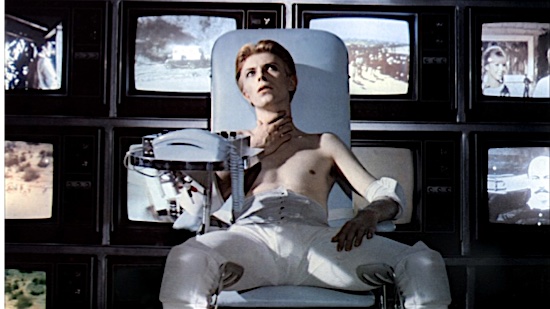

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

Director:

Nicholas Roeg

Imbued with newfound poignancy and melancholia after the passing of its mercurial lead Starman, David Bowie, Nicholas Roeg’s impressionistic, ravenous, experiential masterpiece is one of the rare films about aliens that feels as exotic in its form as its content. Filled with Roeg’s characteristically discursive, paradoxically symmetrical but nonlinear cutting and violently sensual imagery, The Man Who Fell to Earth is as much about subverting the very nature of human experience as it is about offering an outside window into our culture. As the “secretive, but not private” Thomas Jerome Newton—a meteoric billionaire industrialist whose knowledge allows him to skip decades of scientific stranglehold at a mere moment—Bowie’s version of a universal traveler is less about a misunderstanding of the world than a semantic confusion of the pronunciation of words, or an inability to reinforce his own externalized narrative. Even as Newton leaps every known scientific hurdle, his life force is slowly being wrung out by competitors and friends alike who are so consumed with success they’re unable to see the big picture, or recognize the importance of Newton’s own interest in returning to his family.

In what both represents and replicates the experience of watching a Roeg film, Newton obsesses over dozens of televisions, attempting to collectively view reality as one congealed experience. As he explains, “Television shows you everything, but it doesn’t tell you everything.” Moving decades in single frames, Newton can’t escape this misery of his own making, basking in the death of his memories over endless gins as he experiences seemingly multiple lifetimes in a single event. Referring to his eternal imprisonment, Rip Torn’s traitorous Nathan Bryce asks, “Are you mad that we did this?” On the verge of passing out, Newton responds, “We’d have probably treated you the same if you came over to our place.” Even aliens aren’t immune to our vices of apathy and despair. —Michael Snydel

70.

Re-Animator (1985)

Director:

Stuart Gordon

Ironically, the most entertaining take on H.P. Lovecraft is the least Lovecraftian. Stuart Gordon established himself as cinema’s leading eldritch adaptor with a juicy take on the story “Herbert West, Re-Animator,” about a student who concocts a disturbingly flawed means of reviving the dead. Re-Animator more closely resembles a zombie film than the author’s signature brand of occult sci-fi, but it boasts masterful suspense scenes, sharp jokes and Barbara Crampton as a smart, totally hot love interest. Jeffrey Combs as West establishes himself as the Anthony Perkins of his generation, a hilariously insolent and reckless genius he’d go on to play in two Re-Animator sequels. (Combs even played Lovecraft in the anthology film Necronomicon.) Re-Animator is a near-perfect crystallization of the best aspects of ’80s horror, delighting in its perversion as much as its awesomely grotesque practical effects. —Curt Holman

69.

Gattaca (1997)

Director: Andrew

Niccol

Less given to gadgetry and special effects than deeply felt characters, Andrew Niccol’s 1997 film envision a near-future in which almost all children are lab-created and genetically modified to prevent any mental or physical “imperfections.” Ethan Hawke stars as Vincent, a “God child” conceived naturally and therefore irrevocably flawed. In order to pursue his ambitious career dreams, Vincent seeks help from a DNA broker and assumes a new, genetically superior identity. Archetypal in construction, the film uses a beautiful orchestral score by veteran composer Michael Nyman (The Piano) to evoke an atmosphere that both melancholic and reflective, layered over impeccable production design. The film’s every visual element, from color saturation to sound design, assists in immersing viewers in an atmosphere, like those beings one semantic step from being synthetic, simultaneously familiar and completely alien. —Kara Landhuis

68.

Evolution (2015)

Director:

Lucile Hadžihalilovic

Hadžihalilovic’s gorgeous enigma is anything and everything: creature feature, allegory, sci-fi headfuck, Lynchian homage, feminist masterpiece, 80 minutes of unmitigated gut-sensation—it is an experience unto itself, refusing to explain whatever it is it’s doing so long as the viewer understands whatever that may be on some sort of subcutaneous level. In it, prepubescent boy Nicolas (Max Brebant) finds a corpse underwater, a starfish seemingly blooming from its bellybutton. Which would be strange were the boy not living on a fatherless island of eyebrow-less mothers who every night put their young sons to bed with a squid-ink-like mixture they call “medicine.” This is the norm, until Nicolas’s boy-like curiosity begins to reveal a world of maturity he’s incapable of grasping, discovering one night what the mothers do once their so-called “sons” have fallen asleep. From there, Evolution eviscerates notions of motherhood, masculinity and the inexplicable gray area between, simultaneously evoking anxiety and awe as it presents one unshakeable, dreadful image after another. —Dom Sinacola

67.

Twelve Monkeys (1995)

Director:

Terry

Gilliam

Terry Gilliam takes Chris Marker’s La Jetée and makes it grimier. Beginning in post-apocalyptic Philadelphia in 2035, Twelve Monkeys glimpses Earth’s surface as contaminated by a virus that forces survivors to hide underground. Cole (Bruce Willis) must travel back to the ’90s to collect information on this deadly virus, but, of course, nothing goes as planned. While Cole questions his sanity, he must not only find a way to escape the mental institution in which he’s been placed, but he must also race against fate to undo his ultimate undoing. A cauldron of plot twists, excellent performances and environmentalism, Twelve Monkeys makes an inarguable case for inevitable human doom. —Christian Becker

66.

Contact (1997)

Director: Robert

Zemeckis

Contact seems almost calculated as the sort of cerebral sci-fi to frustrate multiplex audiences with its philosophical, open-ended conclusion about “first contact,” questioning whether any of what Jodie Foster’s character experienced really happened at all. Still, Contact is a beautiful film about the struggle between the tangible and the ephemeral, between faith, intellect and ambition. Ellie (Foster) is innately sympathetic, a woman with a selfless streak who nonetheless on some level seeks a very personal validation in being chosen as humanity’s representative to meet an alien race. The film challenges us to consider the depth of our inconsequential standing in the universe, and how different aspects of humanity, both beautiful and hideous, would present themselves after the revelation of a “higher power.” Add to this an impressive cast that includes Foster, John Hurt, James Woods, William Fichtner, Rob Lowe, Tom Skerritt, David Morse and Matthew McConaughey (years before his McConaissance), and you can overlook the presence of Jake Busey in one of the best examples of “hard sci-fi” in the 1990s. —Jim Vorel

65.

THX 1138 (1971)

Director:

George Lucas

The brilliance behind George Lucas’s choice to have his dystopic society disciplined via android cops is that there’s little difference between the machines who keep the “peace” and the people for whom they’re keeping it. Resembling a sort of campy take on highway patrolmen (think the Village People, except with way less singing) spliced with G.I. Joe’s Destro, the robot police force is governed solely on “budget,” which of course allows our hero THX (Robert Duvall) to escape the underground society, and the mysterious deity, OMM 0910, that represses him. Yet, in being left to his own devices after OMM determines that chasing after THX would put the robot police force 6% “over budget,” even THX’s humanity is further reduced to a matter of balancing numbers. It may be a point of triumph for our protagonist, but in perhaps the most subtle thematic move the director has ever made, Lucas is implying that even the organic characters in THX 1138 are mere tools for a higher power. —Dom Sinacola

64.

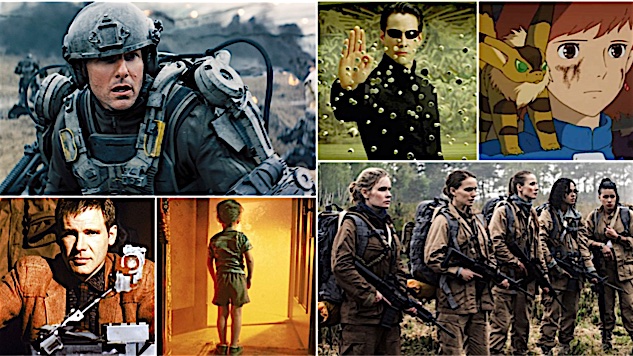

Edge of Tomorrow (2014)

Director:

Doug Liman

Major William Cage (Tom Cruise) spends his days in the film’s near-future setting spinning the armed forces’ ongoing efforts against a hostile alien race (dubbed Mimics) without ever setting foot on a battlefield. At least until a gruff general (Brendan Gleeson) sends him on a particularly dicey mission. The result is Cage’s death, but the story doesn’t end there. Instead Cage awakes at the beginning of the day he died with his memory intact, and quickly discovers the resurrections will recur every time he dies. His only hope of escaping the endless cycle lies with super-soldier Rita Vrataski (Emily Blunt), who knows from experience exactly how Cage might be able to use this new ability to help humanity win the war of the worlds.

Based on the manga All You Need Is Kill by Hiroshi Sakurazaka and adapted for the screen by Christopher McQuarrie (Cruise’s current go-to director completely in sync with his physically-defying action spectacle) and Jez and John-Henry Butterworth, Edge of Tomorrow recalls other notable time loop sagas, including Groundhog Dayand Source Code in the witty and engaging way it moves its story forward piece by piece. As Cage relives the same day over and over again, he also learns how to become a true soldier, trains with (and falls for) Rita, discovers how the aliens function and ever so patiently formulates the perfect plan of attack. Like a video game hero with infinite lives, Cage has the opportunity to refine and correct every mistake he makes along the way. However long Cage is on that journey, Edge of Tomorrow is a blast, and Cruise carries the surprisingly amusing action like a pro—his skill with deadpan comedy proving even more valuable than his infamous enthusiasm for sacrificing his flesh over and over and over. —Geoff Berkshire

63.

Return of the Jedi (1983)

Director:

Richard Marquand

Look, I’m not here to defend Ewoks. Really, I’m not. But there’s a certain subset of Star Wars fans who go really profoundly overboard on their Ewok hang-up. Yes, the little fuzzballs probably could have been phased out of Episode VI altogether, but outside of them, the film offers the most incredible action sequences and epic conclusion of the entire series. So please, forget about the Ewoks for one moment and appraise the film on the rest of its merits.

It’s all here: Incredibly varied settings, from the grime of Jabba’s palace to the overgrowth of Endor and the cold, steely sparseness of Imperial command ships. A fully matured Luke (Mark Hamill) proves that his powers have grown considerably, that he’s not simply chasing “delusions of grandeur” in the rescue of Han (Harrison Ford). And then there’s the true introduction of Palpatine as the face of ultimate evil—is there any more badass way to introduce a character for the first time than for Darth Vader, who we’ve personally witnessed choke numerous officers to death for trivial offenses, to say, “The Emperor is not as forgiving as I am”? The space battle above Endor is the greatest that the series has ever produced, and probably ever will produce (the only thing that comes close is the conclusion of Rogue One); the sheer scale and dizzying choreography that ILM managed to pull off with practical effects in 1983 is still one of the most amazing VFX feats in cinema history. And the ultimate confrontation between Luke, Vader and the Emperor is the tipping point of the entire trilogy’s arc: Luke’s final test—both of his Jedi resolve and his deep-seated belief in the spark of Anakin Skywalker left burning deep within Vader. The moment when Luke casts his lightsaber down and declares himself to be “a Jedi, like my father before me,” bringing a bitter scowl to the Emperor’s crestfallen face, is an emotional triumph. —Jim Vorel

62.

Avatar (2009)

Director:

James

Cameron

It makes sense that Avatar is still the highest grossing movie ever made: Irony and insincerity have no place in its extended universe. Whether or not James Cameron intended to crib the world of Pandora and its futuristic inhabitants from practically every fantastical ur-text ever conceived, it hardly matters, because Avatar is modern mythmaking at its most foundational. Cameron still seems to believe that “the movies” can give audiences a transformative experience, so every sinew of his film bears the Herculean effort of truly genius worldbuilding, telling the simple story of Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) and his Dances with Wolves-like saving of the Na’vi, natives to the planet of Pandora, from the destructive forces of colonialism. Cameron wants us to care about this world as much as Jake Sully, and by extension James Cameron, does, crafting flora and fauna with borderline sociopathic obsessiveness, at the time pushing 3-D technology to its brink to bring his inhuman imagination alive. It worked; “unobtanium” is actually a real thing. Four sequels feels like a disgusting gambit for a man whose ambition may have long ago outpaced his sense of storytelling, or sense of reason, or sense of what our oversaturated, over-franchised culture can even stomach anymore. But Cameron’s proven us wrong countless times before. —Dom Sinacola

61.

Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017)

Director:

Rian Johnson

The Last Jedi, unlike its predecessor, has the freedom to be daring, and perhaps the most thrilling thing about it—and there are many, many thrilling things—is how abundantly it takes advantage of that freedom. If The Force Awakens was basically just Star Wars told again in a new, but familiar way, The Last Jedi challenges the audience, challenges the Star Wars mythos, even challenges the whole damned series itself. It blows the universe up to rebuild it; it is a continuation and a new beginning. And more than anything else, it goes places no Star Wars film has ever dreamed of going. In a way, the success J.J. Abrams had with The Force Awakens, particularly how decidedly fan-servicey it was, laid the groundwork for what The Last Jedi is able to pull off. That movie reminded you how much power and primal force this series still had. This movie is an even more impressive magic trick: It uses that power and force to connect you to something larger. Not everything in The Last Jedi works perfectly, but even its few missteps are all founded in the desire for something new, to take risks, to push an American myth into uncomfortable new directions. —Will Leitch

60.

Dark Star (1974)

Director:

John

Carpenter

The debut of both John Carpenter and writer Dan O’Bannon, Dark Star is, like the ship which bears such a foreboding name, a jalopy cobbled together of sci-fi garbage. A small crew—comprised, notably, of a man (played by O’Bannon) who claims he’s taken the identity of the real sargeant, whom he watched commit suicide; a former surfer and full-time dude, Lieutenant Doolittle (Brian Narelle); and the cryogenically preserved corpse of their former commanding office (Carpenter, getting that SAG card)—cruise the cosmos looking for “unstable planets” to bomb. Complicating the crew’s drudgery is the ship’s constant state of decay, the absolute boredom of their jobs and the fact that their bombs can talk due to artificial intelligence, an existential crisis that does not escape the small, self-aware weapons of mass destruction. Working off of a miniscule student’s budget, Carpenter manages to claim, with uncommon creativity and precision, every sci-fi indulgence and spare idea he can get his mitts on. His omnivorous canon starts here. —Dom Sinacola

59.

Interstellar (2014)

Director:

Christopher

Nolan

Whether he’s making superhero movies or blockbuster puzzle boxes, Christopher Nolan doesn’t usually bandy with emotion. But Interstellar is a nearly three-hour ode to the interconnecting power of love. It’s also his personal attempt at doing in 2014 what Stanley Kubrick did in 1968 with 2001: A Space Odyssey, less of an ode or homage than a challenge to Kubrick’s highly polarizing contribution to cinematic canon. Interstellar wants to uplift us with its visceral strengths, weaving a myth about the great American spirit of invention gone dormant. It’s an ambitious paean to ambition itself. The film begins in a not-too-distant future, where drought, blight and dust storms have battered the world down into a regressively agrarian society. Textbooks cite the Apollo missions as hoaxes, and children are groomed to be farmers rather than engineers. This is a world where hope is dead, where spaceships sit on shelves collecting dust, and which former NASA pilot Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) bristles against. He’s long resigned to his fate but still despondent over mankind’s failure to think beyond its galactic borders. But then Cooper falls in with a troop of underground NASA scientists, led by Professor Brand (Michael Caine), who plan on sending a small team through a wormhole to explore three potentially habitable planets and ostensibly secure the human race’s continued survival. But the film succeeds more as a visual tour of the cosmos than as an actual story. The rah-rah optimism of the film’s pro-NASA stance is stirring, and on some level that tribute to human endeavor keeps the entire yarn afloat. But no amount of scientific positivism can offset the weight of poetic repetition and platitudes about love. —Andy Crump

58.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

Director: Hayao Miyazaki

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is, quite simply, the film responsible for the creation of Studio Ghibli. It not only signaled Miyazaki’s nascent status as one of anime’s preeminent creators, but also sparked the birth of an animation studio whose creative output would dominate the medium for decades to come. Following the release of The Castle of Cagliostro, Miyazaki’s odd Lupin III adventure, the director was commissioned by his producer and future long-time collaborator Toshio Suzuki to create a manga in order to better pitch a potential film to his employers at Animage. What resulted was Nausicaä, a fantasy-sci-fi epic inspired by the works of Ursula K. Le Guin and Jean “Moebius” Giraud, starring a courageous warrior princess trying to mend a rift between humans and the forces of nature while soaring across a post-apocalyptic wilderness.

Nausicaä was the film that introduced the world to the motifs and themes for which Miyazaki would become universally known: a courageous female protagonist unconscious of and undeterred by gender norms, the surmounting power of compassion, environmental advocacy and an unwavering love and fascination with the phenomenon of flight. It spawned an entire generation of animators, among them Hideaki Anno, whose lauded work on the film’s climactic finale would later inspire him to go on to create Neon Genesis Evangelion. The essentialness of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind’s placement within the greater canon of animated film, Japanese or otherwise, cannot be overstated. —Toussaint Egan

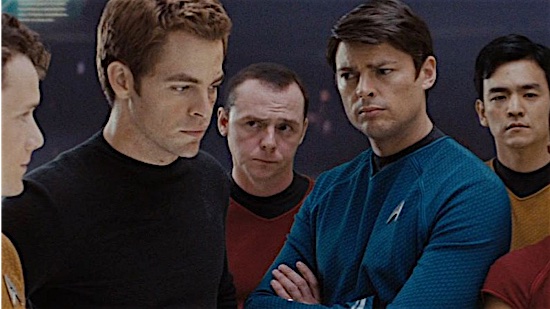

57.

Star Trek (2009)

Director:

J.J. Abrams

J.J. Abrams’ slick movie reboot of the Star Trek franchise is essentially a louder, flashier and sexed-up take on the ’60s television show. While it eschews the series’ usual M.O. of sci-fi-as-social-commentary, it’s largely faithful to the source material and features a top-shelf ensemble cast. Star Trek resurrects the idealistic flights of fancy of pre-’70s sci-fi, and offers us a compelling glimpse at what a multicultural (not to mention multicivilizational) utopian future might look like. Perhaps more importantly, this movie takes a franchise that’s seemingly indelibly stamped with the scarlet letter of geekdom and gives it mass appeal. —Michael Saba

56.

Logan’s Run (1976)

Director:

Michael Anderson

In the far-flung future of 2274, 30 is the new 80. Unfortunately for those who think they’re entitled to a second act in life, like Logan 5 (Michael York), escaping can get you sentenced to “Deep Sleep” by the Gestapo-like Sandmen. And even if you make it past the human assassins, you could still wind up face-to-chrome grill with Box, the magnificently melodramatic robot who ran out of fish! And plankton! And sea greens! And protein from the sea!, and so decided it might as well flash-freeze some fresh Runners instead. I can’t prove it, but I have a sneaking suspicion Billy West modeled his performance of thespian robot Calculon from Futurama after Roscoe Lee Browne’s positively Shakespearean Box. “My birds! My birds! My birds!! —Scott Wold

55.

Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015)

Director: J.J.

Abrams

The Force Awakens provided a remedy for the near-terminal Prequel-itis of fans. J.J. Abrams and company accomplished this act of restorative cinema primarily through a return to the “dirty future” aesthetic that made the Original Trilogy feel so real (no matter how absurd the dialogue being delivered by the characters). That’s not to say CGI is lacking, but whereas budget and technology constraints helped the first three films and an overabundance hurt the next three, the balance between practical and special effects in The Force Awakens feels near perfect. I say “primarily” not to take away from other factors, such as casting. Daisy Ridley, John Boyega and Adam Driver are all solid, and Oscar Isaac brings a palpable vigor to his role. Ultimately, The Force Awakens just feels right in ways the Prequels never did. —Michael Burgin

54.

Men in Black (1997)

Director:

Barry Sonnenfeld

Tommy Lee Jones and Will Smith have tremendous chemistry in what’s essentially a buddy cop movie. But if the cocky, young cop starts out sure of himself, Jones’s Agent K quickly brings him down to an alien-infested Earth. Delightful in tone, director Barry Sonnenfeld plays into all our wildest conspiracy dreams, turning our everyday world into a secret refuge for an imaginative variety of creatures from planets beyond. The plot might be a little slim, but the alien vignettes along the way are clever enough to carry the weight. —Josh Jackson

53.

Minority Report (2002)

Director:

Steven

Spielberg

The more we become connected, the more any sense of personal privacy completely evaporates. So goes Steven Spielberg’s vision for our near future, couched in the signifiers of a neo-noir, mostly because the veil of safety and security has been—today, in 2002 and for decades to come—irrevocably ripped from our eyes. What we see (and everything we don’t) becomes the stuff of life and death in this shadowed thriller, based on a Philip K. Dick story, about a pre-crime cop John Anderton (Tom Cruise) whose loyalty and dedication to his job can’t save him from meaner bureaucratic forces. Screenwriters Scott Frank and Jon Cohen’s plot clicks faultlessly into place, buoyed by breathtaking action setpieces—metallic tracking spiders ticking and swarming across a decrepit apartment floor to find Anderton, the man submerged in an ice-cold bathtub with his eyes recently switched out via black market surgery, immediately lurches to mind—but most impressive is Spielberg’s sophistication, unafraid of the bleak tidings his film prophecies even as it feigns a storybook ending. —Dom Sinacola

52.

Videodrome (1985)

Director:

David Cronenberg

Videodrome wears many skins: It’s a near-future thriller about the lines between man and machine blurring, a sadomasochistic fantasy, a chronicle of one man’s tragic descent into madness and even a screed against society’s abusive relationship with theatrical violence. Yet, more than any dermis it claims as its own, Videodrome is horror down to its bones, a shard of phantasmagorical mania wielded by the genre’s most cerebral master. The mind is where Cronenberg creeps, taking his imagination’s darkest wanderings—steeped in symbolism and subconscious detritus—to visceral extremes. The same could be said for smut peddler Max Renn (the always sweaty James Woods), manager of a cable TV channel devoted to finding new boundary-breaking entertainment, who stumbles upon a pirated broadcast signal carrying “Videodrome,” a seemingly unsimulated series filled with graphic torture and death. As Cronenberg’s dark dreams tend to do, “Videodrome” begins to warp Renn’s reality—our mind’s eye, as one episode explains to him, is the television screen—and the malevolent forces behind “Videodrome” convince him to go on a killing spree, armed with his newly grown mutant cyborg hand (which might be a hallucination but probably isn’t). Throughout, Cronenberg literalizes Renn’s grossest thoughts, opening up a vaginal orifice in his stomach (into which he salaciously sticks his handgun) or transforming his television set into a pulsating, veined organ, manifesting each apocalyptic vision with immediate, tactile reality. In Videodrome, maybe more saliently than in any of his other films, Cronenberg squeezes the ordeals of the slumbering mind like toothpaste from the tube into the disgusting light of day, unable to push them back in. Long live the new flesh—because the old can no longer hold us together. —Dom Sinacola

51.

Soylent Green (1973)

Director:

Richard Fleischer

Cannibalism is usually such an intimate affair. Not so in Soylent Green, a loose adaptation of Harry Harrison’s 1966 novel, Make Room! Make Room!, in which “Soylent Green is people!” Along with his famous call for cleaner, less groping ape hands, Charlton Heston’s delivery of Soylent Green’s signature line has proven one of his most lasting contributions to pop culture, as well as one of the great spoilers of film history. —Michael Burgin